- Mrs. Yetunde Olopade of Nilayo Sports Wins Newstap/SWAN 5-Star Award

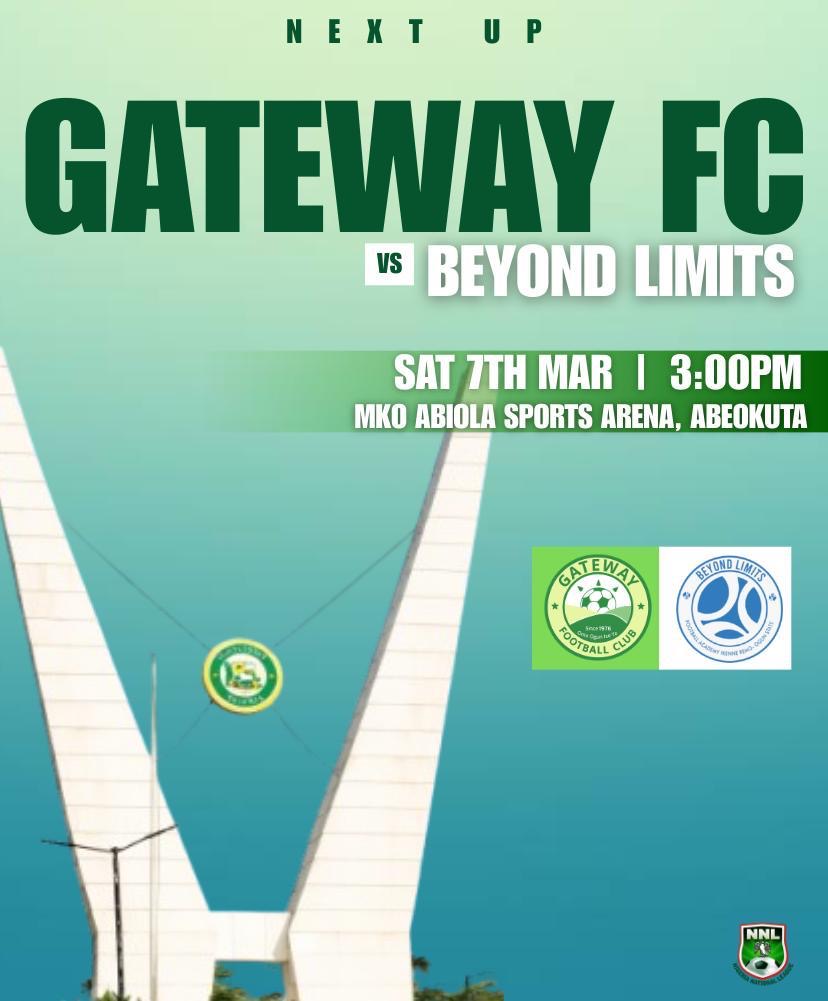

- NNL 2025/2026: Ogun State Showdown; Gateway FC Takes on Beyond Limits

- Freed Actor Baba Ijesha Breaks Silence, Warns of Human Wickedness

- FIBA Rankings: D’Tigers Fall to 53rd Globally

- Police Raid Kidnap Network in Edo, Arrest 65, Recover N1.8m

- Naira Slips Slightly Against Dollar

- Tinubu Sets Up GAMCO Committee to Tackle Stranded Power, Fix National Grid

- Tinubu Approves Posting of 65 Ambassadors to Foreign Missions, UN

- New Study Finds Microplastics in 90% of Prostate Cancer Tumors

- Researchers Push for National Wastewater Surveillance to Catch Outbreaks Early

- Nigeria’s Metering Rate Climbs to 57% as DisCos Add 678,000 Customers in 2025

- Canal+ to Discontinue Showmax After MultiChoice Takeover

- NDLEA Seizes 2.55m Kg of Drugs Worth Over N3tn at Nigerian Seaports in Five Years

- Anthony Joshua Undergoes Rib Treatment and Rehab Following Tragic Accident

- 128 Boxers Battle for 10 Slots at 2026 Commonwealth Games Trials in Lagos

- NSC Gifts Majekodunmi ₦3m as Tour Continues

- NSC Eyes Inclusive Growth at 3rd National Para Games

- Tolu Arokodare Beats Virgil van Dijk as Steven Gerrard Defends Striker

- NFF Dismisses Reports That Super Eagles’ World Cup Hopes Are Over

- CAF Postpones 2026 Women’s Africa Cup of Nations in Morocco

- Senator Seriake Dickson Dumps PDP for Newly Registered NDC

- First Lady Tinubu Hosts State First Ladies on RHI Progress

- President Tinubu Renews Appointment of NIPSS DG Prof. Ayo Omotayo

- Shettima: Tax Reforms Will Ease Burden, Not Impoverish Nigerians

- Presidential Team Joins Strategic Meeting on Non-Kinetic Peace Approaches

- Tinubu Meets ENI CEO as OPL 245 Dispute Ends, Investments Loom

- Nigeria–United States Military Partnership Focused on Training and Intelligence Sharing, Not Establishment of Military Base – Says Defence HQ Spokesman

- Nigeria–US Military Cooperation Centers on Training, Intelligence Sharing — DHQ

- Tinubu Suspends Airport E-Toll Over Flight Disruptions

- Tinubu Sends Five-Member Delegation to Jesse Jackson’s Burial

- Tinubu Swears In Tunji Disu as 23rd Inspector-General of Police

- Cashless Drive: Zamfara Governor Ends Cash Revenue System

- Super Falcons Dominate as Cameroon Fall 3–1 in Yaounde

- Edo Flood Tragedy: Two Children Drown

- NNPC Unfolds 2026 Blueprint to Drive Gas Growth

- Fuel Price Hike Bites Hard in Abuja, Lagos

- From Tax Reforms to Finance Ministry: Oyedele Nominated

- Marafa Records Milestones at RMAFC, Earns Fresh Recognition

- Tinubu Nominates Taiwo Oyedele as Minister of State for Finance

- Ahmed Musa Quashes Transfer Rumours

- Nigeria’s Democracy Gets Fresh Endorsement From UN

- Minister Rallies Youth to Lead Fight Against Fake News

- Gunmen Raid Niger Communities, 15 Feared Dead

- Nigeria Moves to Unlock OPL 245 With Four-Block Development Plan

- Police Council Ratifies Disu as IGP, Tinubu to Swear Him In Wednesday

- The ‘code of silence‘

- The One-Eyed Man

- Oil Climbs Above $72 on Rising Middle East Tensions

- AI-Driven Chip Shortage May Push Smartphone Prices Up 20% in Nigeria

- NESG Urges Nigerian Entrepreneurs to Prioritise Exports and Digital Expansion

- NNPC Targets July 2026 First Gas as AKK Pipeline Spurs Fresh CNG Investment Drive

- Mascot Ikwechegh Quits APGA, Future Party Plans Unknown

- Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei Killed in U.S.–Israel Strikes

- Gen. T.Y. Danjuma Visits President Tinubu at State House

- Tinubu Renews Abubakar Audi’s NSCDC Tenure

- Nigeria’s GDP Hits 4.07% in Q4 2025, Signaling Strong Economic Recovery

- Obasanjo Applauds Naira Stabilisation as Boost for Tinubu Administration

- Hope Uzodinma Fires Up The One message, One Party, One Mobilization Framework movement

- Top Spot Up For Grabs: Beyond Limit FC Takes on Inter-Lagos FC in NNL Showdown

- Stop Lamentation Over Electoral Act, Presidency Tells ADC, NNPP

- Court Voids Malami’s Bail, Orders Remand in Kuje Prison

- Osimhen Slams Gala Squad After Champions League Win

- Nigerian Blind Female Sambists Set to Make History at World Cup

- D’Tigress Announces Provisional Squad for World Cup Qualifiers

- PSG Escape Monaco Test to Book Last-16 Place

- Atletico Boss Explains Lookman Bench Role

- Nigerian Stocks Slip as N73bn Wiped Off Market Value Amid Broad Sell-Off

- ECOWAS Raises Alarm Over Low Uptake of Duty-Free Trade Scheme at Seme Border

- LCCI Backs CBN Rate Cut, Urges Sustained Reforms to Lower Business Costs

- Tinubu Extends Ban on Raw Shea Nut Exports to Boost Local Processing

- PDP Chieftain Urges Probe into Attack on ADC Members in Edo

- Dr. Essiet Begins Citizen-Focused Engagement in Kwara State

- Wike Describes Mpigi’s Death as Loss to Rivers and Nigeria

- President Seeks Constitutional Backing for State Police

- FG Inaugurates CREDICORP Board, Targets Wider Credit Access by 2030

- First Lady Tinubu Honoured as Utukpa-Oritse, Appeals for Unity

- B’Odogwu is Live: Nigeria Launches Digital Customs System to Simplify Trade

- Ray Amodi Leaves Nollywood to Chase Music Career

- CBN Eases Monetary Policy, Cuts Key Rate

- Court Hears Case in Fatal Crash Involving Joshua’s Associates

- Fresh Crude Export Plan Targets Higher Oil Revenue

- Presidency Pledges ₦50M to Fight Social Vices in Schools

- Kalu Seeks Unity in Abia APC, Backs Tinubu 2027

- Tinubu Pushes State Police, Praises NASS Reforms

- Shettima Reaffirms FG Fire Safety Plan, N5bn Relief for Kano Traders

- Tinubu Charges New IGP to Restore Public Confidence, Strengthen Discipline

- Disu Pledges Zero Tolerance for Corruption, Says Citizens Are ‘The Boss’

- AMAC Chair Named North Central Coordinator of RTIFN

- Osimhen in Galatasaray Squad for Juventus Clash

- CBN Slashes Interest Rate to 26.50% in Monetary Policy Shift

- Shettima Highlights Economic Gains, Urges Ambassadors

- Abuja 2026: Facilities Earn High Marks After Para Games Inspection

- Police Shake-Up: Tinubu Accepts Egbetokun’s Exit, Names Disu Acting IGP

- IDA Team Joins 2026 Games as 38th State

- Fresh Drive for Professionalism in Nigeria National League

- 2027 Will Be Referendum on Reform, APC Chairman Tells Strategic Summit

- Uzodimma Unveils Unified Mobilisation Blueprint as APC Targets 2027

- Abia APC to Hold Harmonised Ward, LG Congresses Feb 25–26

- Ighalo and Lawal Back Ademola Lookman for Success at Atletico Madrid

- ‘Handle the Noise or Leave’ – Arteta Issues Bold Challenge to Arsenal Squad

- Jake Paul Undergoes Second Jaw Surgery Following Joshua Knockout

- Sports Federation Bosses Commend Tinubu’s Proactive Reforms in Nigerian Sports

- Cristiano Ronaldo Hits Historic 500-Goal Milestone Since Turning 30

- Lagos Cracks Down on Environmental Hazard, Seals Obalende NITEL Building

- Every Child Counts: Nigeria Records 14 Million New Birth Registrations in Two-Years

- How Pet Cats Are Unlocking New Paths for Human Breast Cancer Treatment

- New Partnership in Kano Set to Bridge Specialist Gap in Northern Nigeria Cancer Care

- Lagos Fortifies Health Defenses as Japan Delivers $1.7m in Cholera Relief

- Ogun Monarch Backs Iyabo Obasanjo’s Governorship, Calls for More Women Leaders

- CJN Kekere-Ekun to Swear In Justice Oyewole as Supreme Court Justice Wednesday

- Ramadan Timing Responsible for Low Turnout in FCT Polls — Bashir Ahmad

- UNICEF Applauds Nigeria’s Surge in Birth Registration

- President Tinubu Celebrates FCT, Kano, Rivers Election Winners

- APC Sweeps FCT Councils, Wike Cites Renewed Hope Momentum

- 2027: Sunday Dare Empowers Ogbomoso Grassroots Team with Campaign Bus

- The Importance of Having Chia Seeds and Milk During Ramadan

- AI Ventures Accelerator Offers $10,000 for Women-Led African Startups

- FG to Review MTN’s $6.2bn IHS Acquisition

- Nigeria Crypto Startups Seek Review of ₦2bn SEC Rule

- Unity Bank–Providus Merger Nears Completion

- FX Access Sparks 366% Rise in Nigerians’ Overseas Travel Spending

- FG Plans N800bn Investment in Agro-Processing, Renewables

- TotalEnergies Targets Near Net-Zero Gas Output

- Global Football Stars Rally Behind Vinicius Jr. Following Alleged Racist Abuse

- Philippe Coutinho Leaves Vasco da Gama, Cites Mental Exhaustion

- Boniface Ruled Out of The Season Despite Rehabilitation Progress

- Adesanya Calls Pyfer Bout His “Biggest Fight”

- Sunday Oliseh Backs Arsenal for Champions League Glory

- Uzodinma Urges Unity Ahead of Imo APC Congresses

- Rivers Assembly Halts Fubara Impeachment Proceedings

- Lagos APC Dismisses Backlash Over Tinubu’s Assent to Electoral Act 2026

- Tinubu, German Chancellor Merz Agree on Security, Power, Rail Cooperation

- Tinubu, Uzodimma, Uba Sani: The Renewed Hope Team Driving National Unity

- NSC Sets Dates, Opens Para Games Portal

- Benin ₦143m Fraud: Two Docked in Major EFCC Crackdown

- El-Rufai in Second Night of EFCC Custody Over ₦432bn Probe

- Frank Onyeka Breaks Silence After Coventry City Championship Debut

- Kano Hisbah Board Restricts Tricycle Operations for Ramadan

- Tinubu Orders Direct Oil Revenue Remittance

- Tinubu Signs Electoral Act Amendment into Law

- President Tinubu Signs Electoral Act Amendment Bill

- Tinubu Urges Unity as Lent, Ramadan Begin Same Day

- Uba Sani Appointed APC Renewed Hope Ambassador

- Tinubu launches national child food bank campaign

- First Lady Calls for Reflection, National Prayers at Start of Lent

- Oluremi Tinubu Urges Prayers for Peace, Prosperity as Ramadan Begins

- Ooni of Ife Adeyeye Enitan Ogunwusi: Summit Drives Health Unity

- Ruler Urges Tinubu to Resolve Kanu Detention Crisis

- Tinubu Cheers Nigeria–UAE Industrial Deal as BUA Seals Abu Dhabi Partnership

- Inflation Eases as CPI Drops to 127.4 in January, Rate Slows to 15.1%

- Mourinho Names Trophy Favourites, Calls Them “Kings”

- National Assembly of Nigeria Approves N1.5tn 2026 Army Budget

- Kenneth Eze Proposes 16-Year Single Term for Presidents

- Customs intercepts suspected cocaine worth N1bn along Badagry-Seme border

- Lagos says 1.5 million residents actively served by public water system

- Report Reveals Costly U.S. Deportations to Third Countries

- Panama opens permanent residence pathway for long-term international students

- Health in the Marketplace: Oyo State’s Bold Outreach at Ajegunle Market

- Fighting for the Fifth Birthday: Experts Call for Universal Sickle Cell Screening

- Taraba’s 14-Year High: The Deadly Cost of Delayed Hospital Visits

- Falconets Overpower Senegal, Set Up World Cup Decider Against Malawi

- Ex-Chippa United Goalkeeper Questions Nwabali’s Shock Exit

- Singapore, Hong Kong Offer Six-Figure Olympic Bonuses

- Peter Obi Confirms 2027 Presidential Bid

- Nigeria Backs AU Peace, Security, and Development Reforms

- Oluremi Tinubu Honors Late Chief Ojora in Condolence Visit

- Tinubu Condoles Kano Traders, Orders Market Fire Probe

- Tinubu Visits Adamawa Monday, To Inaugurate Projects, Meet Leaders

- Kebbi : Beyond Borders, President Tinubu’s Re-opening of the Tsamiya and Kamba borders, a stroke of Economic Diplomacy

- Tinubu Heads to Kebbi Saturday for Project Commissioning, Argungu Festival

- Independent National Electoral Commission Sets Feb 20, 2027 Poll Date

- African Tech Funding Hits Record Low as Investors Turn Cautious

- EU Weighs Sanctions Over WhatsApp AI Restrictions

- Israel Adesanya Hints at Retirement by 2027

- Super Falcons Gear Up for WAFCON Title Defence with Abidjan Tournament

- Frank Onyeka’s Coventry Debut Delayed as Wife Prepares to Give Birth

- CAF Starts Stadium Checks for AFCON 2027

- How traders use triangle patterns to confirm breakouts and manage risk

- Strategic imperatives for investors under Nigeria’s Petroleum Industry Act

- Conoil faces dividend uncertainty amid earnings decline and share price slump

- Dangote Refinery expansion expected to boost output and GDP contribution

- Tinubu Hails BOI’s Record N636bn Loans as Validation of Economic Reforms

- Tinubu Mourns Scholar, Former ASUU President Prof. Biodun Jeyifo

- El-Rufai Condemns Airport Arrest Attempt, Urges Respect for Rule of Law

- Atiku Endorses ADC, Says Party Can “Salvage Nigeria”

- Oluremi Tinubu Named Leadership Newspapers Person of the Year

- Shettima Lands in Addis Ababa for AU Summit

- Sokoto Governor Approves Early February Salaries Ahead of Ramadan

- Nasir El-Rufai to Appear Before EFCC on Monday

- Osayi-Samuel Hails Osimhen as Superior Striker to Haaland

- Peseiro Explains Why Lookman Chose Nigeria Over England

- Kola Daniel Joins 2027 Africa School Games LOC

- Africa Running Conference 2026 Kicks Off in Lagos

- Electoral Act: Real-Time Transmission Does Not Guarantee 100% Transparency — Dare

- Electoral Bill: Akpabio Signals Imminent Tinubu Assent

- EFCC Witness: Banks Behind 2022 Naira Scarcity

- NRS Hits ₦28.3tn in 2025, Targets ₦40.7tn Revenue for 2026

- Bergkamp Predicts Title Winner as EPL Enters Decisive Stretch

- Tinubu Appoints New SHESTCO MD, NEMSA CEO and Board, Sends RMAFC Nominees to Senate

- South East Exclusion Claims Rock Passport Printing Policy

- Real Madrid Dream: Chelle Speaks on Coaching Ambition

- No Romance: KWAM1’s Daughter Dami Dismisses Asake Rumours

- BSUTH Reopens Clinical Services After Resident Doctors Call Off Strike

- Natasha Suspension Stands as Appeal Court Backs Senate

- NIS denies barring any region from passport issuance

- CAC deregisters over 400,000 inactive, non-compliant companies in 2025

- Veekee James and Husband Femi Atere Announce First Pregnancy

- Ebuka Obi-Uchendu Surprises Wife with Romantic Re-Proposal in Vatican City

- As South-East Progressively Aligns With The Tinubu Administration

- EFCC Uncovers N70m POS Fraud Scheme

- Tinubu Celebrates Afenifere Chieftain Abagun Kole Omololu at 70

- Tinubu Launches New Development Push at NEC Conference

- 5 Days to Go: Lagos Braces for High-Stakes Marathon Showdown

- ADC’s Aminu Tambuwal Refuses to Sit Under APC Flag in Viral Video

- SDP’s Adebayo Calls Tinubu an ‘Emperor with Many Servants’

- IPOB Cancels Monday Sit-At-Home in South-East

- NARD Condemns Assault on Doctor at FMC Owo, Demands Compensation

- VP Shettima to Chair NEC Conference on Inclusive Growth

- Kano Pillars, Remo Stars Clash in Relegation Six-Pointer

- Niger Tornadoes Threaten to Withdraw from NPFL Over Stadium Ban

- Bendel Insurance Defeat Enyimba 2-0 as 16-Year-Old Debuts with Goal

- Osimhen Backs Eric Chelle for Long-Term Eagles Role

- Simeone Plans Custom Role for Ademola Lookman After Impressive Debut

- CBN Flags Fintech’s Heavy Reliance on Foreign Capital

- Shettima to Chair NEC Conference as FG Pushes Inclusive Growth Agenda

- VP Shettima Hails Imo at 50, Pledges Increased Federal Support

- Tinubu’s Sports Drive Powers Nigeria’s Davis Cup Return After 19 Years

- Kaduna Ranks 2nd Nationally for Ease of Doing Business

- Leão Honors Ronaldo with Birthday Song at 41

- Ibrahim: Remi Tinubu Boosts Nigeria’s Image

- Matawalle Hosts Joint Wedding Ceremony for Nine Children in Abuja

- Army Dismantles Edo Kidnap Hideouts, Arrests 13

- Tinubu Hails Pate, Makanju Over Devex Power 50 Recognition

- Advocates Call for Local Govt Autonomy to Curb Child Deaths

- Steven Sparks Sparks Debate on Juju and Africa’s Progress

- Juliana Olayode Refuses On-Screen Kisses, Revealing Outfits

- Kunle Afolayan Seeks Divorce to Pursue Polygamy

- Timini Egbuson Laments Losing ‘Soulmate’ to Money

- Simi Slams Critics Using Her Life to Judge Women

- “President Belt” Boxing Championship Set for April in Nigeria

- Ajagba, Itauma, Oshoba Target World Boxing Titles in 2026

- Nigeria Cricket Unveils 2026 Women’s T20I, U-17 Championship

- INEC Endorses Wike-Led PDP Caretaker Committee Amid Party Crisis

- Tinubu Holds Strategic Talks on Tax Reforms with Ombudsman, Finance Officials

- Tinubu Orders Army to Kaiama After Terror Attack

- Stanley Nwabali Leaves Chippa United

- President Tinubu Expands Women’s Economic Programme to 25 Million Nigerians

- Senate Retains Electronic Transmission of Election Results

- The New Aristocracy: When Your Surname Becomes Your Credential

- PUMA Joins Access Bank Lagos City Marathon as Official Apparel Sponsor

- Seyi Tinubu Inaugurates RTIFN State Coordinators in Abuja

- Tinubu-Ojo Receives Ondo Lifetime Award for President Tinubu

- VP Shettima Launches 25-Year South-East Economic Blueprint

- Remi Tinubu Calls for Compassionate, People-Centred Cancer Care

- Gabriel Suswam Dumps PDP, Joins APC

- Wike: FCT Growth Will Not Be Derailed By Politics

- NNPCL Suspends Refinery Operations To Stop Value Erosion

- Abeokuta Hosts Senegal Lionesses Ahead U-20 Falconets Clash

- Tinubu Hosts World Bank, IFC Delegation at Aso Villa

- Tinubu: Nigeria Ready for Secure, Cleaner Energy Push

- Breakdown of Terror Financing Charges Against Ex-AGF Malami, Son

- PDP Crisis Deepens as Umar Sani Faults Court Verdict

- NECO Releases 2025 External SSCE Results, High Pass Rate Recorded

- Lookman Joins Atletico Teammates in First LaLiga Training Session

- Why Kogi’s FAAC Windfall Makes Its Sukuk Plan Untenable

- Dosu Critiques Nwabali’s Approach

- Six Injured in Third Mainland Bridge Bus Crash

- Labour Unions Set Solidarity Rally for Striking FCDA Workers

- Electoral Act Amendment Useless Without Enforcement — Falana

- Nine Suspects Arraigned Over Deadly Benue Attack

- FG Signs MoU, Launches Free Training for 10 Million Nigerians

- Uzodimma to Chair APC 2026 National Convention Coordination Committee

- Ogun Stakeholders Launch Initiative Against Unsafe Abortions

- 5 Essential Habits to Protect and Improve Your Vision

- Parents Raise Fears Over Children’s Development After Vaccines

- Nigerian Built Applications Surpass 1 Million Sales Milestone – NOTAP

- PayPal Partnership With Paga Sparks Debate

- OpenAI to Stop GPT-4o on February 13 as GPT-5 Takes the Top

- NCC Audit Reveals Mobile Coverage Reaches 78% of Nigeria’s Major Roads

- Tinubu Welcomes Governor Kefas to APC, Promises Taraba Development

- 16 Officers to Face Trial Over Foiled Coup – Defence Minister

- Imo State Celebrates 50 Years of Progress and Unity

- First Lady Oluremi Tinubu Marks World Hijab Day 2026

- Nigeria Celebrates World Interfaith Harmony Week 2026, Urges Unity Across Faiths

- Tinubu Hails Fela’s Historic Grammy Lifetime Honour

- Lagos, British Cycling Move to Partner on Knowledge Exchange, Skill Transfer

- SL AKINTOLA – The Thunder Of History

- Nigerian Exchange slips 549 points, struggles to hold 165,000 level

- Accord Confirms Adeleke’s Nomination for Osun Governorship Race

- APGA Releases Timetable for 2026 Anambra LG Primaries

- BUA Foods Posts ₦507.7bn Profit as Strong Sales Offset Rising Costs

- NNPP Faction: Yusuf Left Over Kwankwaso’s Control, Not Ambition

- First Lady Commissions Dream Centre at OAU

- Ibadan Lecture Honours SL Akintola, 60 Years On

- FG Raises ₦501bn Toward ₦4trn Power Debt

- Nigeria on Alert Over Multiple Disease Outbreaks — NCDC

- Nation Loses Industrial Titan as Tinubu Mourns Otunba Ojora

- Shettima Urges Peaceful Coexistence on Palace Visit in Jos

- Diezani Faces Corruption Charges as London Trial Starts

- Atiku Abubakar’s Cognitive Dissonance

- CBN Approves Temporary Use of Expired NAFDAC Licences for Imports

- ‘What I Faced as Super Eagles Coach’ – Oliseh Speaks

- ‘Charade!’ – Kanu’s Lawyers Blast Prison Transfer Hearing

- Wike Stands Firm: FCT Strike Requires Talks, Not Threats

- Lawmakers Back Soludo Amid N19.6bn Market Loss

- Türkiye Targets $5bn Trade Volume with Nigeria – Erdogan

- Mutfwang Joins APC as Shettima Says Party Is Home for All Nigerians

- President Bola Tinubu’s state visit to Turkey: The quick wins

- Tinubu, Erdogan Deepen Nigeria–Türkiye Ties During State Visit

- Alausa Honours First Lady, Prof. Ahmad at National Teachers Summit in Abuja

- JAMB Mandates Live CCTV for 2026 UTME

- NFF, Super Eagles Mourn Ndidi’s Father

- Remembering the Ikeja Bomb Blast: Nigeria’s Dark Sunday of January 27, 2002

- Oluremi Tinubu Urges Shift to Clean Energy

- President Tinubu Beats A New Path In Nigeria Türkiye Partnership Says Presidential Spokesperson, Sunday Dare

- Scientists Uncover Sleep’s Role in Preventing Alzheimer’s

- Delta Backs Cancer Advocate with ₦10m Donation

- NAFDAC Busts Factory Producing Fake Anointing Oil

- Lassa Fever Alarm in Benue: Two Dead as Outbreak Spreads to Health Workers

- 2.5 Million Residents in Ebonyi Struggle with Open Defecation Daily

- LivingTrust Mortgage Bank Posts ₦1.01bn Profit

- NGX Money Market Funds See Strong 2025 Growth

- Google Trends Show Nigerians Focus on Entrepreneurship and Well-Being

- Nigeria’s Currency Outside Banks Hits ₦5.4 Trillion

- Over 94% of Nigeria’s Cash Circulates Outside Banks

- Beatrice Ekweremadu Returns to Nigeria After UK Prison Release

- VP Shettima: Nigeria Reclaims Global Economic Spotlight

- Ex-Defence Chief Warns of Forces Seeking to Destabilise Nigeria

- Musawa Says Atiku Unlikely to Defeat Tinubu in 2027 Elections

- Former Lawmakers Back Tinubu’s Re-Election Ahead of 2027 Polls

- Court Orders 48 to Report to SSS Over Fraud Case

- Ahead Of President TINUBU’S Trip To Turkey, Sunday Dare X-trays The Significance Of The Trip To Both Countries

- Renewed Hope Global Tour Attracts New Investments in Switzerland

- NSC Sets Pre-Games Camp for Team Nigeria

- Nigeria, Türkiye Set for Fresh Strategic Talks as Tinubu Visits

- Tinubu’s Reforms Recalibrating Nigeria’s Fourth Republic, Says Dare

- 21 Days to Lagos Marathon: East, West African Stars Set for Showdown

- From gun-blazing to partners: Appraising President Tinubu’s diplomatic masterclass

- Nigeria’s 4th Republic : What Is Working And What Is Not By Sunday Dare

- Sachet Alcohol: NAFDAC Rolls Out Nationwide Enforcement Drive

- Over 800 Newborn Deaths Daily Sparks National Emergency

- VP Shettima Unveils Nigeria’s Food Security Macro-Strategy at Davos

- Baba-Ahmed: Atiku Better Positioned Than Obi for ADP Convention

- Kano Emir Juggles Royal Duties and University Studies

- FG Pledges Action on Ibadan Floods as Olubadan Seeks Urgent Intervention

- Tinubu Approves Posting Of Four Ambassadors-Designate To Key Global Missions

- Tinubu Targets Jobs, FX with Fresh Push for Deep-Offshore Projects

- Tinubu, Shell in Talks Over $20bn Bonga SouthWest Project

- Tinubu’s Tough Choices Are Fixing Structural Injustice — Dare

- Nigeria Beat Algeria Again, Extend Strong 2026 Start

- Odimayo and the Art of People-Focused Lawmaking

- 11th Access Bank Lagos Marathon to Run on New Route

- Mutfwang Expresses Confidence in Tinubu as Reserves Improve

- Gratitude And Growth: Uzodimma Marks Six-Year Milestone

- Togo Hands Over Former Coup Leader Damiba To Burkina Faso

- March 25 Set For EFCC–Oceangate $13m Case

- Trump Orders Recall, US Envoy Richard Mills Exits Nigeria

- Portable Out On Bail, Ends Week-Long Detention

- Senegal Walkout: Le Roy Breaks Silence On Message To Mané

- WEF 2026: Nigeria Enters Global Economic Spotlight with Davos Pavilion

- NYSC Secures ₦2bn Fund to Support Young Entrepreneurs

- AFCON Triumph Tainted by Senegal Walkout, Infantino Reacts

- Abuja Grinds to Halt as FCTA, FCDA Workers Begin Strike

- Abba Yusuf, Tinubu Hold Closed-Door Talks at Aso Rock

- Borno: Troops Overrun Terrorist Camps, Prevent Major Assault

- Tinubu Congratulates Alake on AMSG Re-Election

- NCR Nigeria rallies 76.8% in 2026 despite weak fundamentals

- Nigerian startup, MAX secures $24m to scale electric vehicle financing

- Lagos Taskforce Arrests Six Over Attacks on Stranded Motorists

- IMF Warns AI Job Disruption Is Reshaping Global Labour Markets

- Kwara Fire Service Averts Disaster as Petrol Tanker Burns in Ilorin

- Kano Governor Orders Manhunt Over Dorayi Family Killings

- Osun Court Remands Five Suspects Over Alleged Ritual Attack on Teenager

- Police Detain 80-Year-Old Man Over Fire That Destroyed Family House in Imo

- FG Sets Up National Task Force to Boost Clinical Governance, Patient Safety — Pate

- ADC Demands Transparency on US–Nigeria Health Cooperation Deal

- Gbenga Daniel Says Nigeria Has Moved Past Its Toughest Period

- Ejimakor Says Kanu Judgment Could Influence Igbo Voting Pattern in 2027

- Otti Says Fixing Abia, Not 2027 Politics, Is His Priority

- More Than Medals: How the Super Eagles’ AFCON Journey Tells the Story of Nigerian Grit

- Tinubu Hails Super Eagles After AFCON Bronze Medal Win

- Shettima Attends Guinea Inauguration, Reaffirms ECOWAS Role

- Tinubu Returns, Nigeria Seals Trade Deal with UAE

- Tinubu Celebrates Bisi Akande at 87

- Yobe State clears N15.4bn gratuity backlog owed to retirees

- Dangote Refinery targets fuel price stability despite global crude oil volatility

- Kano Suspends 3 Health Workers Over Surgical Error Death

- Police Arrest Suspect Over Alleged Acid Attack on Teenager in Adamawa

- Suspected Human Trafficker Nabbed in Makurdi with Seven Underage Boys

- Court Dismisses Akpoti-Uduaghan’s Defamation Case

- Man Hospitalised as Truck Carrying Rubber Materials Catches Fire in Oyo

- Oyedele Denies Suspension of Tax Guidelines

- Baba-Ahmed: Defeat Tinubu Through Action, Not Courts

- Nigeria’s Inflation Hits 15.15% in December

- NEC: Shettima Chairs Council On Ranching, Livestock Development

- Armed Forces Day: Tinubu Honours Fallen Heroes, Backs Military

- Global Travel Disruption As US Pauses Visa Processing In 75 Countries

- TCN Restores Power To Taraba After Prolonged Outage

- World Bank: Tax Reforms to Lift Nigeria’s Growth to 4.4% By 2026

- Catholic Knight Renounces Faith After Cathedral Ignores Ubah’s Legacy

- AFCON Semi: Five POTY Winners Clash

- Nigeria, UAE Seal Major Trade Deal

- Shettima Urges Selfless Service, Celebrates Hadiza Bala Usman at 50

- Tinubu Reaffirms Nigeria’s Net-Zero, Energy Access Goals

- Dollar Pressure Persists as CBN Reforms Tested

- Nigeria Pushes Gas Expansion to End Electricity Outages

- Xabi Alonso Sacked by Real Madrid

- Rema Wins Big with Three Awards at 9th AFRIMA

- Army Saves 18 in Cameroon-Bound Boat Hijack

- Tuggar: Nigeria Seeks Funding, CEPA Deal at Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week

- Tinubu Attends UAE Sustainability Summit

- CBN, NCC to Enforce 30-Second Airtime Refunds

- FCCPC Set To Stop 103 Loan Apps From Operating

- Drama as Portable’s Baby Mama Allegedly Seeks His Arrest

- Victor Boniface Reveals Struggle Behind Injury Smile

- Carter Efe Goes Viral After Revealing Year-Long Single Status

- Barcelona, Real Madrid Set for Super Cup El Clásico

- Purdue Power Past Penn State as Big Ten Race Tightens

- NFL Wild Card Weekend Kicks Off with High-Stakes Clashes

- BUA Chair Rabiu Pledges $1.5m Bonus for Super Eagles’ AFCON Win

- Impeachment Move: Fubara Calls for Calm, Says Situation Will Be Resolved

- Politicians Intensify Pre-2027 Campaigns Despite No Official Election Season

- Democracy Under Threat Began with Atiku, Not Tinubu — APC’s Okechukwu

- Ganduje Returns to Nigeria After Dubai Stay, Set for Key Political Talks

- Nigeria to Face Morocco in AFCON Semi-Final Clash

- Response To KPMG: Observation on Nigeria’s New Tax Laws

- FG Secures Release of Nigerian Pastor in Benin

- Measles-Rubella Rollout Begins in Osun, Expert Assures on Vaccine Safety

- Three Science-Backed Strategies to Optimize Your Digestion

- Analysts, BDCs Predict Stronger Naira on FX Inflows

- Nigeria’s Business Growth Hits 12 Months, Costs Dampen Confidence

- BVN Enrolments Hit 67.8 Million in 2025 as CBN Initiatives Drive Surge

- KPMG Warns New Tax Laws May Trigger Disputes, Capital Flight

- Lagos, UNILAG Strategize Ahead of National Under-18 Games

- AFCON 2025: Super Eagles Barred from Interviews Ahead of Algeria Clash

- Lagos Assembly Approves ₦4.4 Trillion 2026 Budget

- Oluremi Tinubu Appreciates Women Leaders, Calls for Continued Support in 2026

- INEC Urges Lagos Residents to Join Voter Registration Phase 2

- Regina Daniels Threatens Ned Nwoko Over Drug Claims

- Phyna Seeks Reconciliation with Davido Two Years After Online Feud

- Adekunle Gold and Simi Welcome Twins, Expand Family

- Oyo Police Warn Against Drowning Risks

- Tinubu Condoles Chimamanda Adichie on Death of Son

- A Rejoinder to “Bola’s Tax”: When “Simple Logic” Becomes Simple Misdirection

- Doris Uzoka-Anite, CBN Fast-Track FX for Super Eagles Bonuses

- Asari Dokubo Vows Support for Tinubu’s 2027 Re-election

- Court Grants ₦500m Bail to Malami, Wife, Son

- US Imposes Up to $15,000 Visa Bond on Nigerian Visitors

- Dare, Folarin, Fatai Buhari, other APC Leaders rally for TINUBU’S reelection in Ogbomoso

- NFF Welcomes Arthur Okonkwo’s Switch to Nigeria

- FG Targets WAEC, NECO Malpractice with New 2026 Reforms

- Chelsea Confirm Liam Rosenior as New Head Coach

- NYSC Sets Jan 21 for 2026 Batch ‘A’ Stream I Orientation

- Alleged Missing ₦128bn Predates My Tenure, Adelabu Tells SERAP

- APC Rolls Out Statewide E-Registration in Ondo

- Tinubu Seeks Senate Confirmation for 21 Nominees to NUPRC, NMDPRA Boards

- NGX All-Share Index Tops 156,000 in New Year Rally

- NGX Announces Full-Year 2025 Index Review, Adding Guinness Nigeria, Presco, and Wema Bank

- Low-Income Earners to Benefit Most from New Tax Reforms – NRS Chairman

- NNPCL Cuts Petrol Price to N815 per Litre in Abuja

- China Rejects Role of Any Nation as ‘World’s Policeman’

- Lagos Plans N7bn Jetty at Oworonshoki Waterfront

- Bago: Kasuwan Daji Attack Cuts Across Faiths, Communities

- Kwankwaso: I’ll Defect Only for Presidential or VP Ticket

- 2027: I Never Opposed Backing Peter Obi – Momodu

- Maurice Revealed How Crypto Ban Made Yellow Card Stronger

- Cardano, Shiba Inu Dip as BlockDAG Fuels 4,000% Hype

- FG Records 400% Surge in Hospital Visits as 47 Million Receive Life-Saving Vaccines

- Health Crisis Looms as Resident Doctors Set to Resume Indefinite Strike January 12

- Delta Catholic Diocese in Mourning as Priest Slumps, Dies While Preaching at Mass

- Visa Dream Turns Nightmare as Alleged Fraudster’s Actions Earn Nigerian Five-Year Travel Ban

- Benue Attacks: American Visitor Recovers Skeletal Remains in Yelwata Community

- Global Leaders Respond to U.S. Raid on Maduro

- Amorim Blasts Manchester United Officials After Leeds Draw

- President Tinubu Orders Security Agencies to Hunt Kasuwan Daji Attackers

- Why Nigerians Should Support The Tax Reforms

- Distinguishing between Federal Government Revenue and the Federation Account

- Trump: U.S. Forces Capture Venezuela’s President Maduro, Wife

- Wabara Debunks Defection Rumours, Affirms PDP Loyalty

- No More Free Handouts – Tonto Dikeh Draws the Line for 2026

- CBN Releases 2026 Outlook, Maps Growth Path

- Anthony Joshua’s Driver Charged After Fatal Nigeria Crash

- IMPRISONED BY AMBITION : Peter Obi’s Reckless Misreading of Politics and Power

- Nigeria’s Telecom Giants Move from Survival to Growth

- Starlink Hits 9 Million Users Globally As Nigeria Becomes its Stronghold in Africa

- Chelle Closes Super Eagles Training Ahead of Mozambique Clash

- Ranchers Bees Sign Yusuf Musa for Second Half of NNL Season

- Oluremi Tinubu Welcomes Nigeria’s First Baby of 2026 in Abuja

- A Golden Run: 2025 and the Year Nigerian Sports Found its Smile Again

- NDLEA Nabs 1,389 Suspects, Seizes Over 7.7 Tonnes of Drugs in Kano

- Tragedy in Ohio: State Reports First the first child death from Flu

- Onuigbo Endorses Tinubu for 2027, Cites Economic Achievements

- Plateau Governor Mutfwang To Join APC Today

- Uzodimma Urges Vigilance to Sustain Peace in Imo State

- De Angels Sends a Stern Warning to Those Circling Her Marriage

- Funke Akindele’s Behind The Scenes Hits ₦1B, Breaks Records

- Nigerian Equities Soar in 2025, NGX All-Share Index Up 51%

- Naira Posts First Annual Gain Since 2012, Closes 2025 at N1,429/$1

- How Verve Became the heartbeat of Nigeria Commerce

- Governor Mutfwang Set To Pick APC Membership Card

- Wike Accuses Fubara of Backtracking on Tinubu-Brokered Peace Deal

- Alex Otti to Stay in Labour Party Despite Obi’s Exit

- Nigeria to Enforce New Tax Laws as FG Pushes Revenue Expansion

- CBN Projects Stronger Economic Growth, Easing Inflation Outlook

- Sydney Talker Speaks on Carter Efe’s Move to Streaming

- Jada Pollock Criticises Acceptance of ‘Side Chick’ Culture

- Yvonne Jegede Clears Air on Annie Idibia Rumours

- “No Mother Can Be at Peace” — Regina Daniels Speaks on Custody Battle

- Nigeria’s E-Commerce Boom Creates Opportunities as bitMARTe Launches

- Microsoft and FG Train 4 Million Nigerians To Gain Tech Skills in Five Years

- 2025: Lassa Fever Deaths in Nigeria Reach 195 in December Surge

- Beyond the Hype: 5 Scientific Backed Health Resolutions for Nigerians in 2026

- NAFDAC Warns: Urgent Alert Over Counterfeit ‘Kiss’ Condoms in Nigerian Markets

- The Summits That Defined Nigeria’s Tech Ecosystem in 2025

- Anambra Becomes Third State to Adopt Harmonised Tax Reform Law

- Over N25 Billion Raised Through Oluremi @65 Education Fund

- First Lady Oluremi Tinubu Urges Nigerians to Embrace Unity and Hope in 2026

- NNPCL Posts ₦502bn November Profit Despite Lower Output

- Allwell Ademola’s Brother Slams Nollywood Stars Over Lack of Support

- Shaffy Bello Says She Avoids Long Road Trips in Nigeria

- Nasarawa Police Ban Tyre Burning During New Year Festivities

- Peter Obi Defects to ADC Ahead of 2027 Elections

- New Tax Laws to Take Effect January 1, 2026 as Planned — FG

- Tinubu Congratulates Wale Edun on Royal Victorian Order Honour

- Tinubu Appoints Rotimi Oyedepo as DPP

- NPFL Talents On Radar Of Foreign Scouts

- Telecom Operators Promise Better Service Nationwide

- Outrage Over Rumours Of Mohbad’s Wife Giving Birth Years After His Death

- Nigerian Boxers Record Wins On Global Stage

- Universities Brace For New Admission Guidelines

- Naira Holds Firm As CBN Tightens Market Oversight

- Tinubu Phones Anthony Joshua, Mother After Ogun Crash, Assures of Best Medical Care

- NSC DG Olopade Visits Anthony Joshua, Mourns Crash Victims

- Gov. Aiyedatiwa Signs N524B 2026 Budget Into Law

- Tinubu Condoles Anthony Joshua Over Lagos–Ibadan Expressway Tragedy

- Nigeria: Close Of Year Accounting Sequencing From Reform To Relief

- Anthony Joshua Injured in Ogun Crash That Claims Two Lives

- Shettima: Strong Marriages Vital to Nigeria’s Development

- Tinubu Departs for Europe, Heads to Abu Dhabi for Sustainability Summit

- Tinubu Joins Historic Return of Eyo Festival in Lagos After Eight-Year Break

- Nigeria–US Airstrike Hits Terrorists in Sokoto, No Civilian Casualties

- Bassey Reveals Near Career Exit Before AFCON 2025 Breakthrough

- Police Nab Notorious Bandits, Recover Arms and Ransom in Kwara

- CAN Hails Tinubu Over Peaceful Christmas

- SGF Akume Marries Former Ooni’s Queen Zaynab

- FG Confirms January 2026 Start for New Tax Laws

- Tinubu Applauds $1.126bn Lagos–Calabar Highway Financing

- 2025 in Review: Sunday Dare, Tinubu’s Media Shield

- Sanusi Praises Otti, Says Abia’s Progress Gaining Global Attention

- 2Baba: No Such Thing as a ‘Wack’ Artiste

- Enyimba Set to Unveil Deji Ayeni as New Technical Adviser

- AFCON 2025: Boubou Traore to Referee Super Eagles vs Tunisia

- Uyo to the Future: Lawson Hezekiah Drives Tech Education with Mita School

- Presidency Debunks Reports of Gbajabiamila’s Replacement as Chief of Staff

- Tinubu Sets Up APC Peace Committee

- Tinubu Calls for Peace, Religious Tolerance in 2025 Christmas Message

- Oluremi Tinubu Calls for Unity, Peaceful Coexistence in Nigeria

- Security Tops Agenda As FG Moves From Promises To Action

- Tough Choices, New Direction: Nigeria Unveils Sweeping Fiscal Reset

- No Drug Test, No Job: FG Sets New Rule For Public Service Recruitment

- Dangote Launches Hotline to Report PMS Overpricing

- NIN Becomes Tax ID for Individuals, CAC Number for Firms – FIRS

- Tinubu Presents National Honour Certificate to Troost-Ekong

- NAF C-130 Resumes Ferry Flight After Precautionary Landing, Crew Safe

- Uzodimma Empowers 10,000 Artisans to Boost Imo Economy

- Tinubu’s Reform Agenda Targets Stronger, More Resilient Nigerian Economy

- Doris Ogala Freed After Two Days In Custody

- Nigeria Stays 38th in FIFA Rankings

- Kwara Governor Presents ₦644bn 2026 Budget to State Assembly

- FG Declares Dec 25, 26 and Jan 1 Public Holidays

- Golden Girl, Florence Oluwadamilanre Strikes Triple Gold in Weightlifting

- Toptier Sports Management commends NSC DG Bukola Olopade as its 40 billion Naira investment set to revolutionize Nigerian Leagues

- Tinubu Renames Azare Health University After Sheikh Dahiru Bauchi

- Tinubu Commends Zulum, Commissions Projects In Borno

- Kaduna Extends Teachers’ Retirement Age To 65

- NAFDAC Bans Indomie Vegetable Flavour

- Tinubu Warns Governors on LG Autonomy Ruling

- AFCON 2025 Kicks Off in Style as Davido Headlines Opening Concert

- Police Nab Suspected Serial Rapist in Sokoto

- NPFL: 3SC Assure Fans of Safety Ahead of Tornadoes Clash

- Nigeria Tax Reforms Is Overdue

- TAX REFORMS PUSH-BACK: Opposition’s Political Gimmickry or Genuine Love for the Masses?

- Tinubu Unveils ₦58.18trn 2026 Budget, Targets Stability and Growth

- FEC Approves N58.47trn 2026 Budget, Revises Exchange Rate to N1,400/$

- NSC Salutes Ahmed Musa for Outstanding Service to the Nigerian Football

- Sunday Dare: Inflation Falls to 14.45% as Tinubu Reforms Gain Traction

- President Tinubu Reconstitutes NERC Board

- Nigeria Clinches 8 Golds in African Youth Games Weightlifting

- Olalekan Reaches Boxing Semi-Finals at African Youth Games

- Tinubu Nominates Successors After NMDPRA, NUPRC Chiefs Resign

- Malaria Transmission Falls in Lagos, FG Says Elimination Within Reach

- AFCON 2025: Nnadi Reacts to Surprise Super Eagles Call-Up

- Falana to AGF: Prosecute 10 Soldiers, 400 Terror Sponsors

- Ganduje: Why We Shelved Private Hisbah to Preserve Peace in Kano

- FG Begins N758bn Pension Bond Disbursement

- Reps Raise Alarm Over Discrepancies in Gazetted Tax Laws

- Court Orders Detention of Vessel Over Cocaine Seizure

- Nigeria’s Q3 2025 Imports Rise to N161.23tn

- Road Safety First: FRSC Issues Warning to Peller

- Team Nigeria Clinches Bronze In Judo At 4th African Youth Games

- Inside the Dangote Remarks, the Regulator, and the Presidency’s Red Line

- Senate Passes 2026–2028 MTEF, Clears Path for Tinubu’s 2026 Budget

- Mikel Questions AFCON Squad as Onyeka Targets Glory

- FIFA Unveils 2025 Men’s Best XI, Luis Enrique Honoured

- Dollar Trades at ₦1,485 at Black Market as Forex Pressures Persist

- Nigeria Earns ₦12.8tn from Crude Oil Exports in Q3 2025 — NBS

- Nova Bank Opens Regional HQ in Owerri

- Tinubu Mobilises Military Assets, Unveils New Armoured Vehicles

- Tinubu Defends Institutional Independence Amid Opposition Outcry

- Tinubu Urges Youth to Learn from Buhari’s Legacy

- Tinubu Hails Buhari’s Integrity, Legacy at Biography Launch

- Dangote Refinery to Sell Petrol at N739/Litre

- NSIB: Eight Escape Unhurt in Aircraft Incident at Kano Airport

- ICPC Recovers ₦37.44bn, $2.35m in 2025

- Lagos Bill Seeks to Ban Evictions Without Court Order

- Canada to Open Express Entry for Foreign Doctors in 2026

- Ebonyi Gov Approves ₦150,000 Christmas Bonus for Workers

- Dangote Alleges NMDPRA Chief Spent $5m on Swiss School Fees, Urges Probe

- 4th African Youth Games: Nigeria’s Medal Surge Continues

- 2025 Africa Youth Chess Championships

- Military Rescues Kidnapped Woman in Taraba

- Ayra Starr Reveals Struggles in New York

- Tinubu Approves Massive Boost to CCB Budget, Raising It to N20 Billion

- Adeboye Urges Faith in God’s Power to Transform Lives

- Uzoho Arrives Early at Super Eagles AFCON Camp

- NDLEA Arrests Suspected Drug Supplier to Bandits in Niger

- ECOWAS Leaders Gather in Abuja for 68th Ordinary Session

- Nigeria Wins 11 Athletics Medals at African Youth Games

- Nigeria’s Young Swimmers Shine at Africa Youth Games

- Lagos Assembly Passes Amotekun Law to Boost Security

- Tinubu to Transform NIPSS into Digital Global Think Tank by 2030 — Shettima

- Tinubu Congratulates Oyebamiji, Calls for Unity Ahead of Osun 2026 Poll

- Shettima Hails Uzodimma at 67, Lauds APC Leadership

- Obasanjo, Gowon, Ooni Grace State House as First Lady Hosts 2025 Christmas Carols

- Kano Govt Bans Independent Hisbah Group

- Sunday Dare: Petrol Price Drop Linked to Tinubu’s Oil Reforms

- Nigeria Wins Hosting Rights for 2027 AU Sports Council Policy Meeting

- Africa Youth Games: Team Nigeria Adds to Medal Tally

- Renewed Hope Ambassadors Drive Nationwide Awareness on Tinubu’s Renewed Hope Agenda

- Tinubu Support Group Names Magaji Da’u Aliyu Deputy DG (North)

- 4th African Youth Games: Nigeria Claims Silver in Badminton, Records Strong Performances Across Events

- Nigeria Submits Bid to Host 2031 African Games

- Hope Uzodimma: Securing The Mandate To Preach The Gospel Of Renewed Hope

- Nigeria Starts on High Note at Africa Youth Games

- First Lady Hosts Children’s Christmas Brunch

- Fani-Kayode, Dambazau Given Ambassadorial Clearance

- FCCPC Takes Action Against Ikeja Electric

- Klint Da Drunk Reveals Why He Abandoned Music for Comedy

- Nigeria Falls One Spot in New FIFA Women’s Ranking

- Tinubu Moves to Resolve Contractor Payment Delays

- 3MTT Summit: Tijani Showcases Tinubu’s Digital Impact

- Bayelsa Deputy Governor Hospitalised After Office Collapse

- Tinubu Unveils New Security–Economic Blueprint to Harness Marine Wealth

- FEC: Tinubu Orders Training, Arming of More Forest Guards

- Team Nigeria Heads to Angola for Africa Youth Games

- Tinubu: Youth Will Drive Nigeria’s Future Through Innovation and Skills

- Nigeria-U.S. Ties “Warm and Robust” – Spokesperson

- Uzodimma, Sanwo-Olu Engage CBN on Growth Strategies

- NRHA Launches Nationwide Renewed Hope Outreach

- Nigerian Equities Fall After Seven-Month Winning Streak

- Wale Edun: Imo Poised for Investment Growth

- Odey Leaves Randers After Four Years

- Piqué Lists Top Contenders Against Barcelona

- Akinsanmiro Called Up for AFCON 2025

- 82 BDCs Approved Under CBN Guidelines

- NAF Clarifies C-130 Diversion

- NUPRC: Govt Slashes Oil Licensing Bonus to $3–7m

- Odumeje Dares Pastors to Miracle Face-Off

- Nasboi Opts for Money in ‘Next Life’

- Yakubu Wins AGN Presidency Over Rita Daniels

- Tinubu: All Kidnapped Students Must Be Returned

- Neymar Plays Through Injury to Save Santos

- Cross River Declares 20-Day Holiday Leave for Workers

- NASS to Debate 44 Constitution Amendment Bills

- Two Killed in Head-On Collision on Sagamu–Benin Expressway

- TikTok Blocks Late-Night Live Streams in Nigeria

- Tinubu Praises Nigerian Forces for Thwarting Benin Coup

- Messi Praises Alba and Busquets After MLS Cup Win

- Odimayo Meets Okitipupa Stakeholders, Seeks Re-Election Support

- VP Shettima in Abidjan for Ouattara Inauguration

- NSA Ribadu Holds Security Talks with U.S. Lawmakers

- Super Eagles’ AFCON 2025 Group Rival Names Provisional Squad

- New CBN Cash Withdrawal Limits Take Effect Jan 1

- NSC, Games LOC Chair Meet on Abuja 2027

- Food Prices Fall Again Nationwide as Tinubunomics Gains Momentum

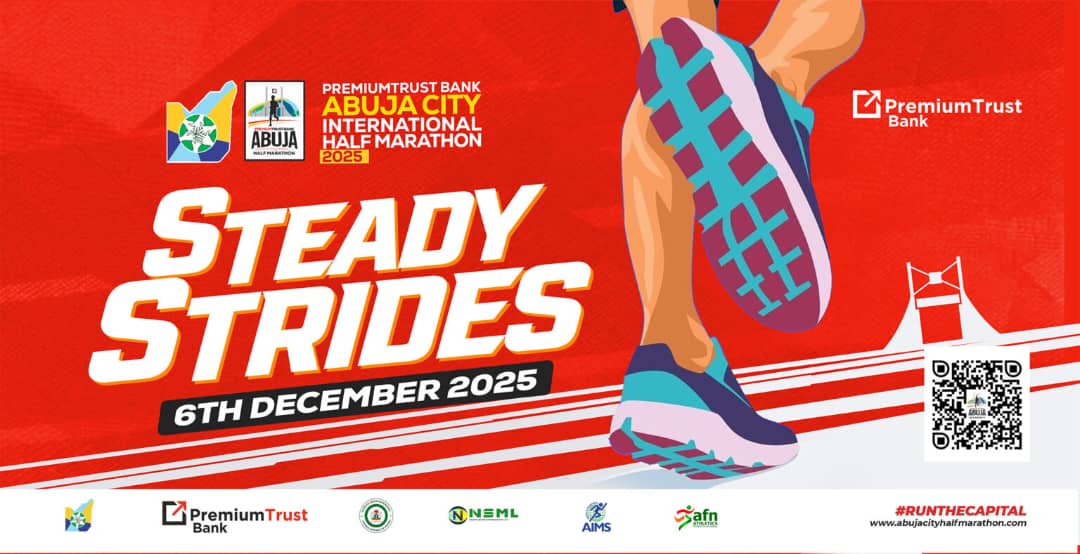

- Kenya’s Namutala, Jepkemoi Win 2025 Abuja Half Marathon

- Nigeria Will Defeat Insurgency, Says Uzodimma as He Calls for a More United Nation

- Tinubu Names New Boards for UBEC, BOA, NADF

- Dangote: Fuel Queues Over, Refinery to Lead Global Output by 2028

- Omisore, Six Others Disqualified from Osun APC Primary

- “Don’t Demarket Imo State” — Leo Stan Ekeh

- Regarding The 2025 Imo State Economic Summit

- Gen. Musa: Security is Everyone’s Responsibility

- Kukah Backs Tough Measures to Restore Security

- Tinubu Swears In Gen. Musa as Defence Minister

- Tinubu Nominates Ibas, Dambazau, Enang, Ohakim as Ambassadors

- “Imo Has Risen and Is Open for Business” — Uzodinma

- When Elders Forget Their Own Footprints, A Nation Suffers the Burden of Selective Amnesia

- Owerri Agog as Imo Economic Summit Begins

- Abuja Ready for PremiumTrust Bank Half Marathon

- Nigeria Dominates Inaugural West Africa Para Games in Abeokuta

- Tinubu Swears In New Permanent Secretaries, NPC Chairman at FEC

- FEC Approves 2026–2028 Fiscal Plan

- NEC Approves Security Funding

- Oluremi Tinubu Calls for Stronger Disability Inclusion in Nigeria

- Akwa Ibom Bans Street Masquerades

- Senate Begins Screening of Defence Minister-Designate Musa Today

- Burna Boy to Fund Funerals of California Shooting Victims

- CBN Raises Withdrawal Limit to ₦500,000

- Obasanjo Cannot Escape Blame for Today’s Turmoil — Omirhobo

- Abuja Half Marathon: Nigeria Gears Up for Elite Field

- Uzodimma Condemns Assaults on Schools, Religious Centres, Labels Perpetrators National Foes

- Tinubu Launches 2026 Armed Forces Remembrance Emblem

- Tinubu Nominates Gen. Musa as Defence Minister

- Nigeria Extends Lead at West Africa Para Games

- NSC to Approve Flag Football Federation, Elections Ahead

- Defence Minister Badaru Abubakar Resigns on Health Grounds

- Oluremi Tinubu Urges Renewed Push to End HIV by 2030

- Shettima Endorses Localised Smart Class Plan for Schools

- Yusuf Alli: Abuja Half Marathon Set for Record-Breaking Return

- Between Tinubu’s Capacity And The Ignobility Of Pseodo Statemanship

- Jonathan Returns Safely, Meets Tinubu Amid Bissau Turmoil

- Tinubu Sends 32 New Ambassadorial Nominees to Senate for Confirmation

- Tinubu Hails Nigeria’s Return to IMO Council After 14 Years

- Tinubu Sets Up National Tax Policy Implementation Team

- NSC Announces Organizing Committee for 2027 Africa School Games

- Enugu State Government nullifies underage marriage, arrest parents, groom and matchmaker

- Another milestone – Automotive Skill Upgrade and Certification Programme for Youths

- Tinubu Sets Up Nigerian Team for US-Nigeria Security Working Group

- Tinubu Declares Security Emergency, Orders Mass Recruitment

- Tinubu Appoints New Ambassadors

- SECURITY THREATS: You Are Doing Well, And We Believe You Will Do More

- Oluremi Tinubu to Global Educators: Let Humanity Lead Technology

- Shettima Returns After G20, AU–EU Missions

- Breaking: All 24 Abducted Maga Schoolgirls Rescued

- Court Orders Nigerian Army To Vacate Disputed Land In Plateau

- Sunday Dare to Deliver Keynote on Youth and Automotive Innovation in Ibadan Tomorrow

- I Won’t Relent Until All Nigerians Are Protected Under My Watch— President Tinubu

- Tinubu Names Uzodimma Renewed Hope Ambassador, DG for APC Outreach

- Nigeria Pushes Africa-Led Security, UN Veto Power at AU–EU Summit

- Nigeria Is Fighting for Its Survival and the United States Must Not Stand Aside

- South-West Governors Unveil Regional Security and Economic Plan

- Nigeria, US Strengthen Security Partnership Following High-Level Talks

- RHAN: Tinubu’s Security Reforms Deliver Major Gains

- Abeokuta Set for Historic West Africa Para Games

- D’Tigers Hit Tunis for 2027 World Cup Qualifiers

- 2Baba, Edo Lawmaker Natasha Osawaru Welcome First Child

- Tinubu Withdraws Police From VIP Protection

- Tinubu Convenes Emergency Security Meeting

- Shettima Heads to Angola for AU-EU Summit

- Nigeria Makes Historic Debut in IBSF World Cup 2-Woman Bobsleigh

- Tinubu Announces Rescue of Kwara Worshippers, 51 Niger Students

- Nigeria Breaks Record with 30-Medal Islamic Games Finish

- Tinubu Urges Fair Mineral Trade, Ethical AI, and Financial Reform at G20

- Shettima To Represent Tinubu At G20 Summit In South Africa

- Abeokuta Set for Historic West Africa Para Games as 10 Sports Debut in 5 Days

- Adewale Leads Lagos APC E-Registration Push

- Odimayo Emerges as a Defining Force in Grassroots-Focused Leadership

- From U.S. Alarm to Tinubu’s Validation

- Tinubu Halts Foreign Trips as Surge of Attacks Sparks Urgent Security Push

- Schoolgirls Abducted: Tinubu Deploys Matawalle to Kebbi

- FAAC Allocates N2.094trn to FG, States, LGs

- Banks Notify Customers as FIRS Enforces 10% Withholding Tax on Fixed-Income Interest

- CBN Warns Public Against Zuldal MFB

- Riyadh 2025: Nigeria Adds Two More Gold Medals

- Congressman Moore Meets Nigerian Officials on Security

- Tinubu Approves Redeployment of 16 Permanent Secretaries

- Tinubu Delays Summits, Orders More Troops To Kwara

- Jigida Queen Tells Lawyer Giwa to Face Court, Stop Media Spin

- Nwoko Rules Out Reconciliation, Says Regina Needs Therapy

- VDM Apologises After Mid-Air Clash With Mr Jollof Disrupts Asaba–Lagos Flight

- Nnaji Rejects Stereotyping of Igbo Women Online

- Hakimi Wins 2025 African Player of the Year

- G20: President Tinubu looks beyond Geo-Politics towards a global economic reset that reflects Africa’s strategic value

- Congratulations, Minister Wike – Dr. Muiz Banire

- Tinubu Sends Shettima to Kebbi, Vows Swift Rescue of Kidnapped Schoolgirls

- Shettima: Tinubu’s Reforms Unlocking Major Investment Opportunities

- Tinubu: Reforms to Boost Youth Competitiveness

- APC Postpones Kefas Reception After Kebbi Schoolgirls’ Kidnap

- Tinubu To Embark On G20, AU-EU Mission

- First Lady Salutes Security Efforts, Receives Chiefs’ Wives

- 25 Kebbi Girls Kidnapped, Vice Principal Killed – First Lady Reacts

- Understanding Hotel Event Pricing Key to Avoiding Hidden Costs

- Nigeria’s Inflation Drops to 16.05% in October 2025

- Okon-George Leads Nigeria Into Three Finals at Riyadh 2025

- Four Nigerians Make Final CAF Awards Shortlists

- Ibrahim Chatta Charges ₦5 Million Per Day in Nollywood

- Abideen Hits Brace as Fomget Rout Unye Kadin 8–0

- Balikwisha Rejects ‘Voodoo’ Claims After DR Congo’s Win Over Nigeria

- Nigeria Confronts Growing Threat of Misinformation

- Prince Edward Visits President Tinubu in Abuja

- Tinubu Warns Fragmented Markets Threaten Trade

- Over 2,800 Runners Register as Abuja Half Marathon Enters Final Countdown

- INEC Releases Full Timetable for 2027 General Elections

- Tinubu Opens 2025 Judges’ Conference, Vows Stronger Judicial Reforms

- Tinubu Steps In: Military Veterans Get Long-Awaited Pension Arrears After Peaceful Protest

- 2027: Peter Obi Poised to Rejoin PDP as Party Commits to Southern Zoning for Presidential Ticket

- New DGSS Assumes Office

- Farewell to a Titan: Nigeria Mourns the Passing of Edwin Clark

- The Delta Exodus: A Wake-Up Call for PDP?

- Tinubu Declares “The Worst Is Over” as Nigeria Marks 65 Years of Independence

- 18 Africans Among 135 Cardinals Eligible to Elect Next Pope

- FG Scrambles as N4 Trillion Debt Pushes Power Sector to the Edge

- AFCON Drama: CAF To Rule On Lybia VS Nigeria Showdown After Chaotic Qualifier

- Nigerian Education Loan Fund Disburses 2.5bnTo 22,120 Students

- Tinubu’s Bold Plan: How Livestock Investment Could End Farmer-Herder Conflicts And Hunger In Nigeria

- A House Divided: The Untold Story Behind Dajoh’s Fall

- First Bank Set to Build Nigeria’s Tallest Tower—A Game-Changer for Banking and Lagos Skyline

- Energy Monopoly Showdown : Oil Marketers Fight Dangote Refinery’s Bid To Control Nigeria’s energy Sector

- Nigeria’s Multi-Million Dollar Plan to Revolutionize Public Broadcasting

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Iconic Kenyan Author and Activist, Dies at 87

- PRESIDENT TINUBU DEPARTS ABUJA TO BEGIN 2025 ANNUAL LEAVE

- Lagos State Sports Commission upholds Dissolution of Senior Team Lagos, Warns Impostors Parading as Lagos Athletes

- AfroBasket 2025: D’Tigers Crush Defending Champions, Tunisia to Record Second Group Win

- Tinubu, Sanwo-Olu Laud Doctor’s Guinness Achievement

- FG Approves N758 Billion to Pay Off Pension Debts—Here’s When Retirees Will Get Paid

- Wike Vows To Continue Abuja Demolition Despite protests, Says No Amount Of Blackmail Will Stop Us

- A Decade of Excellence: Celebrating 10 Years of the Access Bank Lagos City Marathon

- Lawmaker Alleges Corruption and Threats in House of Representatives Committee Probe

- Muhammed Babangida Embraces BOA Role, Debunks Rejection Rumors

- December 2024 Revenue Drop: FG, States, LGAs Share N1.424 Trillion Amid Economic Shifts

- BOMB THREAT in Canada: Operations back to normal after multiple Canadian airports hit with bomb threats

- Budget at Risk: Nigeria Misses 2025 Oil Production Target as Prices Slide Below Benchmark

- APC National Chairman Visits Plateau seeks spiritual and royal blessings

- Meet Sunday Akin Dare: President Tinubu’s New Special Adviser on Public Communication and Orientation.

- Nigeria Pledges Additional $500 Million to AfDB’s Nigeria Trust Fund

- President Tinubu Joins Global Leaders in UAE for Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week

- OBITUARY: Aminu Dantata, Kano billionaire businessman who owned lands ‘all over the world’

- Old Naira Notes Still Legal Tender: CBN Sets the Record Straight Amid Cash Scarcity

- RENEWED HOPE WARD DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM

- China Joins Forces with Nigeria to Power $20 Billion Ogidigben Gas Project

- Suspension Holds as Senate Recesses: Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan Locked Out Until September Abuja

- Africa’s Tourism Sector Set to Create 80 Million Jobs in a Decade – CBAAC

- 39 Killed in Abuja, Anambra Stampedes

- Lookman’s Win No Surprise — NSC DG

- Tinubu’s Reforms, Adeola Gaffe: Key Takeaways

- Tinubu’s 2025 Agenda Unpacked

- Musk Introduces Party to Challenge GOP, Democrats

- Oyebanji Backs Tinubu as Boldest Hope

- Zenith Bank’s Dividend Payout Delights Shareholders

- Appeal Court Reinstates ACP Idachaba, Fines Police ₦2m

- Corps Members Set to Get N77k Backlog

- Dr Victor Omololu Olunloyo: Uncommon Brilliance

- NSC Boss Praises Gov Mbah’s Strides

- AFDB Trains Covenant University Students in Data Skills

- El-Rufai Expelled by SDP, Banned for 30 Years

- UNIMAID ASUU Calls Buhari Renaming “Provocative”

- Political Drama in Rivers: Budget Uncertainty as Assembly Adjourns Indefinitely

- Nigeria Customs Service Launches 2025 Recruitment Drive

- Robots Deployed to Prevent Bridge Collapses

- Food Security and National Development in NW Nigeria (2015–2023)

- Akpabio Speaks on Senate Harassment Allegations

- Fuel Frenzy: South Africa And 6 Other Nations Queue For Dangote Refinery’s Fuel Supply

- Tinubu’s Nigeria Defies the Naysayers—Global Investors Are Taking Notice

- FGN URGES ASUU TO SHELVE STRIKE IN THE INTEREST OF STUDENTS, VOWS TO INVOKE NO WORK, NO PAY RULE

- Eastern Rail Rebirth: $3B Secured as Senate Approves Tinubu’s $21B Global Loan Package

- CSOs Are the Backbone of Democracy – Presidential Aide Sunday Dare Declares

- Signs of Recovery? Naira Begins to Stabilize as Oil Production Rises

- Foreign Fighters Fueling Terror: DHQ Blames Influx for Northwest, Northeast Attacks

- Cash Crunch Chaos: Nigerians Struggle as Banks Ignore CBN Orders Amid Yuletide Rush”

- Sadiq Khan Hails Lagos as ‘Africa’s Cultural Capital’ as He Launches First Trade Mission to Africa Lagos, Nigeria

- Tinubu Names Shamseldeen Ogunjimi as Acting Accountant General Amid Treasury Reform Agenda

- PDP Mulls Peter Obi, Jonathan for 2027 Presidential Ticket – Gov Bala Mohammed

- Chiamaka Nnadozie- A Goalkeeper On Another Level Of Qualities And Greatness

- Nigeria Surpasses OPEC Oil Quota as Inflation Dips to 22.22% in June

- FG Sign Massive $328.8 Million Power Deal with China.

- ACADEMIC STAFF UNION OF UNIVERSITIES REJECTS FG LOAN SCHEME, CALLS FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF AGREEMENTS.

- WE’RE BETTER OFF TOGETHER, PRESIDENT TINUBU TELLS MALIAN LEADER

- Forging Ahead: The Evolving Nigeria-South Africa Alliance

- President Tinubu Drives AKK Gas Pipeline to 83% Completion, Set for November 2025 Milestone

- Mass Deportation Shocks Illegal Immigrants in Nigeria

- How to Get FG’s CALM Fund Loan for CNG Conversion & Solar Power—No Collateral Required

- NSC DG Hon. Bukola Olopade Graces Isimi Lagos Festival, Says NSC Will Support Private Sector-Driven Sports Development

- House Of Reps Set For Explosive Showdown Over Tinubu’s $2.2bn Loan Request: Will It Pass Or Spark Chaos

- NCS Generates N1.75 Trillion in Q1 2025 Revenue

- Regina Daniels Drops Bombshell: Don’t Let Your Boyfriend Stop You From Meeting Your Husband Sparks Reactions

- Tragedy in Sokoto: Nigerian Government Promises Probe Into Deadly Airstrike That Killed Civilians

- Apologize and Return? Akpabio’s Media Aide Says Suspended Senator Natasha Holds the Key to Her Own Comeback

- CBN Shakes Up NIRSAL Leadership, Sacks Executive Directors

- JAMB Orders Re-Exam for Nearly 400,000 Students After 2025 UTME Tech Glitch

- Nigeria Introduces Utapate, A New Low-sulfur Crude Grade

- Unveiling The Shadows Of Corruption In NNPCL

- One year later, what value has Tinubu added to our lives? – 1

- EFCC Uncovers Chinese-Led Cybercrime Syndicate: Shocking Details of Abuja Raid

- FG Eyes Fresh $1.75bn World Bank Loan Despite 40% Revenue Surge

- How Top Government Agencies Are Secretly Violating Federal Character Rules

- FG, FAO Unveil N200 Million Initiative to Boost Fish Farming and Cut Imports

- Warri-Itakpe Train Service Returns After Setbacks — Now Running 6 Days a Week”

- Chief Sunday Dare Congratulates Dr Saka Balogun, On His Appointment As Balogun Of Ogbomoso land.

- ECA Urges Bold Action to Transform Africa’s Food Systems

- Election Storm In Ondo: Shettima, APC In Final Push As PDP Cries Rigging Plot

- FG Pledges 14-Month Completion of Abuja-Kaduna-Kano Road Upgrade: What You Need to Know

- Professors on Peanuts: ASUU Warns of Fresh Strike as Varsity Pay Crisis Deepens

- Kaduna And Zaria Erupt In Chaos As Protest Intensify, N700bn Lost In 5 Days

- Activist Arrested Ahead of Anti-Police Protest: Inside the Drama Over Planned Demonstration Against IGP Egbetokun

- Governor Dapo Abiodun Adorns Name “Omobowale” on Two-Time World Heavyweight Boxing Champ, Anthony Joshua, New Boxing Hall Named After Him

- Court Orders Army General to Forfeit N5bn Shares in 17 Companies

- Tinubu’s Surprise Palliative Gift to Christians & Muslims in South-East, South-South

- Fears of Nationwide Protest Triggers Fuel Scarcity.

- Military Intercepts 3 Drone Strikes, as BH Upgrades Warfare.

- 2Face’s ‘African Queen’ Crowned No. 1 on Billboard’s Afrobeats All-Time Songs List

- Tinubu’s Bold Housing Move: Why Town Planners Are Applauding His Latest Appointment

- El-Rufai’s Political Capital Crashes: Mahdi Shehu Warns Opposition Against “Suicide Alliance”

- INEC Launches AI Division to Transform Nigeria’s Electoral System

- Nigeria to Launch Massive Space-Tech Training for Youths – 200,000 to Benefit Annually

- Expert predicts Naira Comeback As CBN Slashes Customs Duty Rate

- Nigeria to Host 2027 African Schools Games After Successful Bid

- Ahead of Crucial World Cup Playoffs: What the Super Eagles’ Journey Means for Nigeria

- Abia NMA Slams FG’s Pay Circular, Backs Nationwide Ultimatum

- Downstream Deregulation: Between Obasanjo’s Half-measures And Tinubu’s Bold Leadership

- 14 Days to Go: Ogun State Ready to Host Nigeria’s Biggest Sports Festival Yet

- Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement replicated in Nigeria? What do you think?

- Falana Rejects Planned Protest– ” I will not join the protest. The Leaders are faceless”

- Matawalle – Nigeria’s Civilian General still at Work

- Why FG Hasn’t Started Direct Allocation to Local Governments

- Desperate Struggles: How Borno’s Refugees Are Battling Survival in Kano’s Shadows

- Tinubu’s Bold Plan: Stabilising West Africa and Uniting Africa’s Troops Through Camaraderie and Fitness

- Tinubu’s Road Revolution: Umahi Unveils Major Infrastructure Push in Southeast

- The SkillUp Imo Project is not just ambitious — it’s visionary. A bold, strategic leap into the digital future. Its target of upskilling 50,000 young people in key digital competencies has been fully realized.

- **Kenya’s Edwin Kibet Wins 10th Access Bank Lagos City Marathon in Stunning Fashion**

- What rising oil prices mean for Nigeria’s fiscal position, stable naira

- Osimhen Scores Twice To Lead Galatasaray Win, Dedicates Goal To Injured Icardi

- Lagos Set to Welcome International Athletes for 10th Access Bank Lagos City Marathon

- Sunday Dare appointed as Special Adviser to the President on Public Communication and Orientation

- NIGERIA’S NON-OIL REVENUES POWER STRONGEST FISCAL PERFORMANCE IN RECENT HISTORY

- Subversive Elements and Genuine Suffering: Unpacking the Complexity of Nigeria’s Protests

- Jonathan Laments Culture of Betrayal in Nigerian Politics

- Tinubu Assembles Top Industry Experts with Stellar Reputations for NNPCL Board

- Court Ruling Clears Jonathan to Contest Presidential Election Again

- Kubwa, Abuja building collapse casualties unknown

- THE 15 PERCENT ON PETROL AND DIESEL IMPORTS- A BRIDGE. NOT A BURDEN.

- Tinubu Not Settling Tribal Scores

- Federal Gov’t Flags Off TVET Entrance Exam Into Tech Colleges For 30,000 Students

- Nationwide League One Approves Black Scorpions FC’s Relocation to Abuja

- Tax Reform Tug-Of-War: How Nigeria’s VAT Battle Could Reshape The Nation’s Future

- NATIONAL SPORTS COMMISSION

- Olugbon’s Regrettable Stance On Ogbomoso Imam Tussle

- Rivers State Governor Siminalayi Fubara Reflects On Overcoming Impeachment Plot

- Bola Tinubu : A President Ready To Risk It All For Future Generations

- Kayemo Exposes Major Air Travel Secret: Oyedepo’s Jet Can’t Take Off Without Proper Approval

- Attom Foundation Brings Barça Legends and African Legends to Abuja for Champions Cup*

- Nigerian Civil Servants To Receive Enhanced Salaries After Minimum Wage Adjustment

- Cabinet Shake-up : Tinubu’s Bold Moves Spark Division Between Private Sector And Opposition

- 123 Million Liters Of Petrol Imported As Marketers Race To Meet Demand Amid Dangote Refinery Shortfall

- 70 Dead, 57 Injured in Devastating Tanker Explosion”

- World Para Powerlifting Championships: Nigeria Moves to Second on Medals Table, as Esther Onyeama Strikes Double Gold

- Nigeria Records 39 Mpox, 5,951 Cholera Cases

- PRESIDENT TINUBU’S STATEMENT ON THE PASSING OF HIS MAJESTY OBA SIKIRU KAYODE ADETONA, THE AWUJALE OF IJEBULAND

- Nigeria to Participate in Maiden African School Games in Algeria*

- Trump’s Tariffs Won’t Hit Africa Hard, Says WTO DG Okonjo-Iweala

- Dubai-Based Human Trafficker Nabbed in Abuja After Years on the Run

- Kingsley James Awodi Honored with Prestigious Sportsville Award

- Food Crisis: Register Online For N40,000 Rice– FG Tells Public Servants t

- Tinubu Warns: Lake Chad Region Must Unite or Risk Chaos

- Fundamentals About “State of Emergency” Declared on Nigerian Oil and Gas by NNPC

- NIGERIA’S SPORTS REVOLUTION: THE UNPRECEDENTED ₦78 BILLION BUDGET THAT IS SET TO USHER IN FRESH SPORTS DISPENSATION

- Meet Mallam Musa Kida. Newly Appointed Chairman of the NNPC BOARD.

- Nigeria’s Rebased GDP Hits ₦373 Trillion—Now Africa’s 4th Largest Economy

- Davido, Tems, Rema Shine at 17th Headies Awards

- No Place for Xenophobia in Ghana, President Mahama Assures Nigerians

- Nigerians to Pay More? SEC Moves to Tax Cryptocurrency Transactions with New Rules

- Big Tax Breaks Coming: FG To Offer 50% Tax Relief For Companies Boosting Workers Pay

- (50)

- NSC DG Hon. Bukola Olopade Calls for Greater Collaboration in Nigerian Sports Sector, Felicitates With Christians on Christmas Celebration

- AANI Lagos mourns President Buhari

- Tinubu: Northern Development Is Key To Nigeria’s Success, Youths Are Our Present And Future

- Ended Fuel Subsidy to Save Nigeria’s Future– Tinubu Declares as He Rallies Youths for National Development

- Lagos Government Uncovers 176 Unauthorized Estates, Issues 21-Day Compliance Ultimatum

- CAF Reconsiders Rules As Judgment nears I’m Lybia-Nigeria Airport Saga: Will Sanctions Be Imposed?

- Ex Sports Minister Dare Offers Condolences to Babangida Family After Tragic Accident

- Tinubu to sign tax reform bills Thursday

- Presidential Adviser, Sunday Dare, CON, Says Nigeria’s Economy is responding well to President Tinubu Reforms and the Signs cannot be ignored

- FG Cracks Down on Abandoned Oil Assets

- Storm Over Shehu Buba: Terror Links, Church Demolition, and Sectarian Tensions Rock Senator’s Image

- New British Prime Minister Starmer and Challenges Ahead

- Lagos Hits Record Highs: 3.5 Million Children Vaccinated for Measles, 20.3 Million Residents Protected Against Yellow Fever in 2024

- FG Stops Sagamu-Iperu Road Project Over Poor Workmanship — Umahi Issues 7-Day Ultimatum

- Food Importers Must Sell 75% Of Items At Approved Markets, Says Customs

- World Bank Under Fire: Shehu Sani Accuses Institution Of Prolonging Nigeria’s Economic Hardship

- Court Nullifies Benue Chief Judge’s Removal, Rebukes Governor Alia and State Assembly

- Done Deal: Flying Eagles Forward Kparabo Ariheri Signs Pre-Contract With Norwegian Club Lillestrøm Sportklubb

- Shape Up or Ship Out: Akpabio Warns Senate Committees Over Poor Performance

- Honourable Sunday Dare Hails Nigeria’s Journey Of Unbroken Democracy, Commends President Tinubu’s Visionary Leadership

- NATIONAL SPORTS COMMISSION PRESS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS UNIT

- Democratic Silence On Kamala Harris Speaks Volume.

- Edo Government Slams Governor-elect Okpebholo: Focus On Your N5bn Inauguration, Not Obaseki

- FG Joins Forces with UK in Groundbreaking Digital Security Pact

- 10 ways the Tax Bills will make states richer

- Power Shift: North-Central APC Bows to Tinubu, Ganduje in Stunning U-Turn

- PDP Weighs Automatic 2027 Presidential Ticket for Jonathan Amid High-Level Talks

- Ex-Lagos Speaker, Aide Discharged of Lingering Money Laundering Suit

- Tinubu Assembles Top Brass, Ex Governors To End Benue Killings.

- NSC DG Warns Super Eagles B Against Complacency Ahead of Crucial Clash Against Ghana

- A Final Farewell in Daura: Stories, Tributes, and the Quiet Legacy of Muhammadu Buhari

- Tinubu Tax Reforms Bills Debates A Beauty Of Democracy

- PRESIDENT TINUBU RETURNS TO ABUJA FOLLOWING AQABA PROCESS MEETING IN ROME

- FG Approves Expansion Dredging at Lekki Deep Seaport to Boost Vessel Capacity

- Shocking: police Officers Caught Protecting Foreign Hackers On Illegal Duty, Says IG

- A Truly Honourable Man at 69! When his name appeared on the list of ministerial nominees, the natural assumption was that he would head the Ministry of Information. That assumption was not misplaced.

- Tinubu’s Tax Reforms: A Threat to Northern Prosperity? Gov Zulum Sounds the Alarm

- Saraki, Ned Nwoko Weigh In: Reactions Trail Delta State Governor’s Defection to APC

- PDP Slams Peter Obi Over One-Term Presidency Promise

- NSC Mourns the Passing of Legendary Super Eagles Goalkeeper, Peter Rufai

- from the Pulpit to the Pit: Governor Alia and the Blood-Stained Silence of Benue

- PDP Governors Decry Militarisation of By-Elections, Warn Against Plots to Derail Convention

- PRESIDENT TINUBU APPOINTS MUHAMMAD BABANGIDA CHAIRMAN OF THE BANK OF AGRICULTURE, OTHERS AS CHAIRMEN AND HEADS OF GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

- WITHDRAWAL OF REGISTRATION CERTIFICATE OF THE NATIONAL YOUTH COUNCIL OF NIGERIA (NYCN)

- IBB Breaks Silence on Executing Childhood Friend: ‘It Was Him or Nigeria’—Vatsa’s Family Demands Justice”

- Team Nigeria Jets Out to Annaba, Algeria for Inaugural African School Sports Championship

- NSC Explores Sustainable Private Sector Driven Funding Models For Greater Sports Development

- Former Minister Sunday Dare Hails President Tinubu’s N2trn ESP.

- Sanusi Lamido Speaks Truth to Power: Tinubu’s Economic Reforms Are Nigeria’s Only Hope*

- Breaking! NAFDAC Storms Enugu Market – Seals Fake Alcohol Shops, Advise Nigerians on Food Storage

- National Assembly Set to Pass Tax Reform Bills This Week

- ASUU ISSUES NOTICE OF INDUSTRIAL ACTION By Yemi Kosoko

- Sahel On The Brink:Nigeria Faces Growing Threats Amid Regional Instability

- How CBN Saved Nigeria from 42.81% Inflation Disaster – Cardoso Reveals Shocking Figures”

- Nigeria to Unmask Terrorism Financiers Soon – Defence Chief

- Tin City Warms Up for President Tinubu as North Central Embraces Renewed Hope

- FG to Cement Makers: Slash Prices To 7000 Or Face the Heat

- Federal Government Unveils Multi-Million Dollar Fund to Power Nigeria’s Creative Sector

- A Nigerian Marshall Plan Is Needed Today

- Senate Gives Green Light to Tinubu’s $21 Billion Global Loan Deal, Paves Way for 2025 Budget Rollout

- ACF: Time For Work, Not Distractions. Tinubu unstoppable

- PRESIDENT TINUBU NOMINATES NEW CEO, COMMISSIONERS FOR NERC

- Nigeria’s Ambassadorial Void: Tinubu Prepares To Appoint Envoys Amid Diplomatic Uncertainty

- Federal High Court Declares Lakurawa Sect a Terrorist Organization in Landmark Ruling

- DG NIA Tenders Resignation

- President Tinubu Joins Leaders in Tanzania for Game-Changing Energy Summit

- RESPONSIBLE CRITIQUE REQUIRES FACT-DRIVEN NARRATIVES

- ASUU Vows Legal Battle Over UNIMAID Renaming: “This Is a Violation of Our Identity”

- Olukoyede Orders Investigation Of N15million Bobrisky’s Allegations Against EFCC Officers

- Dj Cuppy’s Marriage Wishlist: ‘Seek God Before You Find Me’ Sparks Online Debate

- NLC Rejects Proposed Salary Hike for Political Officeholders, Calls It “Insensitive

- Tinubu Leads as ECOWAS Confronts Regional Crises at 66th Summit

- ALAKE, AFRICAN MINING MINISTERS PLAN TOUGHER RULES FOR VALUE ADDITION

- Sunday Dare Inspects NASENI’s Scientific Efforts

- GOVERNOR AIYEDATIWA CONSTITUTES MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE FOR ONDO STATE FOOTBALL AGENCY

- FG Launches Bold Plan to End Maternal Deaths in Nigeria

- Judicial Firestorm: Afe Babalola Moves to Block Bestseller Exposing Alleged Courtroom Manipulations

- Attack on Free Speech or Justice Served? Atiku Demands Immediate Release of Dele Farotimi

- Security Agents Rescue 20 Abducted Medical Students, Kill Suspected Kidnapper

- PRESIDENT TINUBU EULOGISES SON, SEYI, AS HE CLOCKS 40

- Kaduna Tanker Collision Sparks Explosion, Four Hospitalised

- BUHARI’S LEGACIES WILL CONTINUE TO INSPIRE. – Chief Bisi Akande.

- Bloody August: Amnesty International Accuses Nigerian Police Of Killing 24 Protesters In Crackdown

- Jigawa Assembly Approves Powerful Hisbah Board Law—Here’s What It Means for Residents

- 5 Million Students in Lagos to Get Laptops and AI Training in $1 Billion Digital Revolution

- FG Finally Pays November Salaries After Unexplained Glitch

- BREAKING NEWS: Chanchaga Local Government Chairman Suspended by Legislative Council

- FG Says Lagos-Calabar Coastal Highway Can Withstand Floods for 50 Years

- Sticks Can’t Stop Terrorists” — Ndume Demands Armed Community Defence After Borno Massacre

- PRESS RELEASE Niger Delta Sports Festival Opens in Grand Style, NSC Hails Effort as aligned to RHINSE Initiative

- 48-Hour Showdown: Lawmakers Threaten to Cut Funding for NPA, NIMASA, FIRS, and Other Defiant Agencies

- Anthrax Alert: Deadly Outbreak Hits Zamfara, Nigerians Urged to Stay Vigilant

- NGF Condemns Deadly Attacks in Benue State, Stands in Solidarity with Victims

- Nigeria Joins BRICS as a Partner Country

- Nigeria-Ghana Row: Calm Amid Storm as Ministers Tackle Deportation Rumors

- Fuel Relief for Nigerians: Petrol Prices Drop as IPMAN Partners with Dangote Refinery

- As President Tinubu Takes charge. Rivers Gets a shot at Peace

- Former Minister Sunday Dare Pays Tribute To Soun Of Ogbomosho Land

- She Thrives On Toxicity – Uche Ogbodo Blasts May Edochie And Her Fans In Fiery Rant

- Dangote’s Refinery Dream : A Bitter-sweet Victory For Nigeria’s Economy

- “You Can’t Be Trusted” – Presidency Slams Peter Obi Over One-Term Pledge

- FCT Workers Mobilise For Mass Action Over N70,000, Wage Delay.

- “North Leads in Student Loan Applications as FG Begins Disbursement”

- President Tinubu to Address Nigerians in Landmark June 12 Speech

- Tinubu Declares Economic Turnaround at Ramadan Iftar

- ABU Zaria Secures €5M Grant to Pioneer AI-Powered Microscope for Disease Diagnosis

- BREAKING: Presidency denies finance minister’s alleged N105,000 minimum wage proposal

- Asaba 2025: Delta State Set to Host National Youth Games from August 29 – Sept. 6

- Tinubu Honoured with Lifetime African Achievement Award at Grand Ceremony in Ghana

- FG Terminates Benin – Sapele – Warri Road Contract.

- NNPC, Akwa Ibom, GACN Seal $3.5 Billion Deal to Drive Gas

- One year later: what value has Tinubu added to our lives? –2

- Solid Minerals MoU: France Not Taking Over Nigeria – Presidency

- NiMet Warns of Dust Haze Threats to Flights and Drivers”

- Quiet Cracks: Inside the rumoured Tinubu–Shettima rift

- FG Races Against Time to Rebuild Collapsed Taraba Bridge

- Navy Bolsters Sea Defenses: 1,814 New Recruits Join the Fight Against Piracy

- EFCC Declares Four Wanted Over Alleged CBEX Fraud

- FG Deploys Drones for High-Tech Digital Mapping of Abuja

- NIGCOMSAT Unleashes Space-Tech Hackathon for North-East Youths

- NSC DG, Hon. Bukola Olopade Felicitates with Muslim Faithfuls on Eid-el-Fitr

- Buhari Congratulates Tinubu on One Year in Office, Urges National Unity and Support

- Akpabio: Nigerians Reclaimed Democracy Through Struggle, Not Military Benevolence

- TRUTH BE TOLD , FINIDI IS NOT READY FOR THE SUPER EAGLES JOB

- The Weak and the Liar: A Tale of Two Presidents on the Road to 2024

- Lagos Govt Rushes to Fix Open Manhole After Viral Outcry

- Ibadan Airport Set to Launch International Flights by June 2026

- Nigeria’s $50 Billion Space : Can Satellites Unlock the Country’s Economic Future

- Solomon Dalung: How I was abandoned by hospital for four hours over non-payment of deposit

- FCTA Intensifies Abuja Cleanup, Warns Against Shielding Criminals Under Military Cover

- Dangote Pushes For Fuel Independence As Tinubu Summons Key Players In Nigeria’s Energy Crisis

- Lagos Begins Construction of West Africa’s Largest Psychiatric Hospital to Tackle Gambling Addiction

- JUST IN: NDLEA promotes 5,042 officers, Marwa presents 70 personnel, others with special awards

- Tinubu Orders Revocation of Illegal Lagos Land Approvals as Federal Probe Expands

- Tony Elumelu Foundation Empowers 3,000 African Entrepreneurs

- NSC Showers Praise on Eniola Bolaji and the Badminton Federation After Gold Medal Triumph*

- President Tinubu’s Commitment to Sports Development Delivering Results at the Grassroots Level — NSC Chief Olopade

- Team Nigeria school sports contingents arrive home after impressive outing at inaugural school sports games

- Ademola Lookman Scores Again, Leads Atalanta To Road Victory Against Stuttgart

- Building Digital Momentum: Progressive Digital Media Summit- Sunday Dare

- NewsBudget: We’ll ensure no part of Nigeria is neglected – NASS

- APC NEC convenes July 24 to decide Ganduje’s successor

- FG to hold manufacturers, importers responsible for plastic pollution