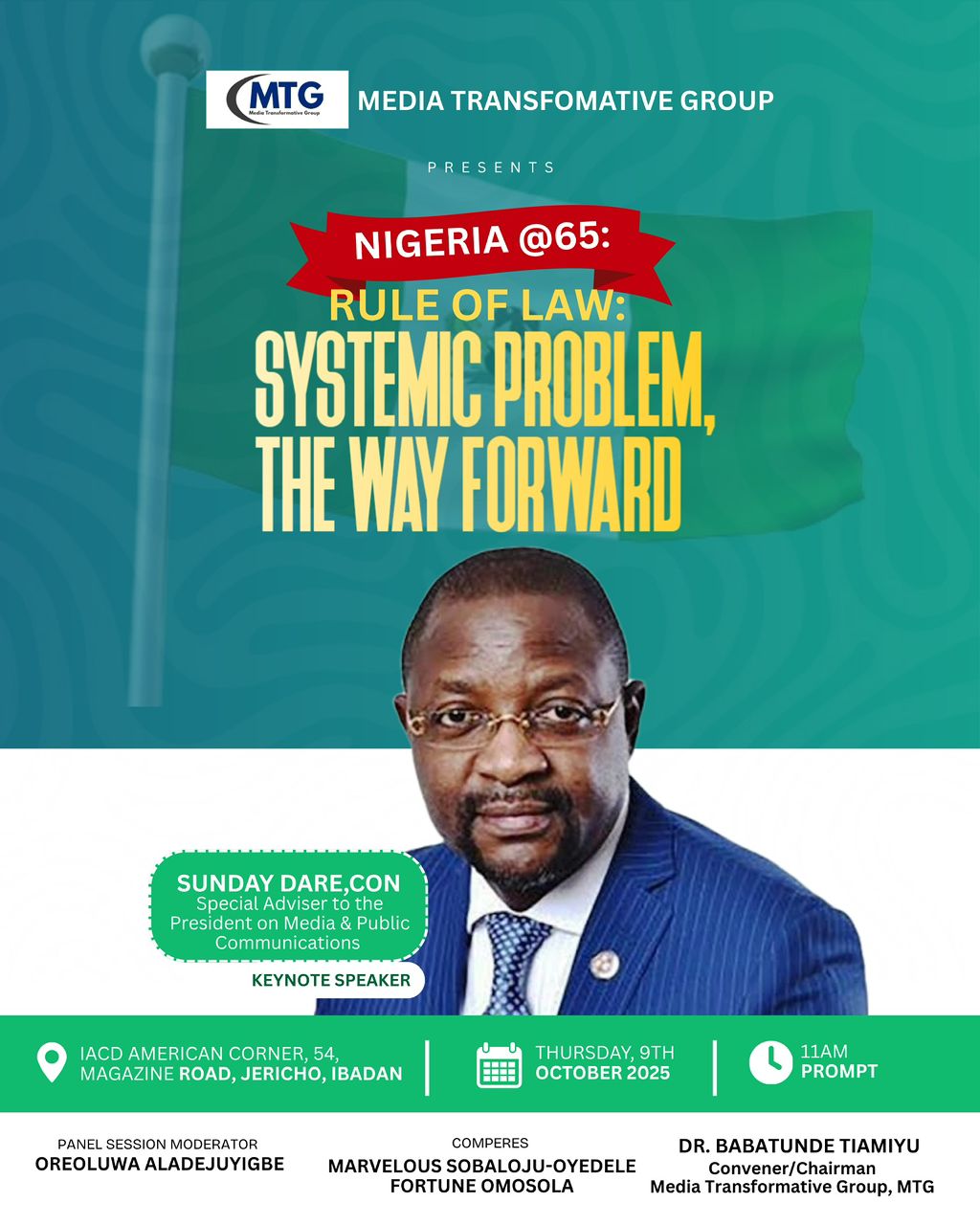

KEYNOTE ADDRESS BY SUNDAY DARE AT THE MEDIA TRANSFORMATIVE GROUP SUMMIT FOR NIGERIA @65 WITH THE TOPIC:Rule of Law: Systemic Problem. The Way Forward

KEYNOTE ADDRESS BY SUNDAY DARE AT THE MEDIA TRANSFORMATIVE GROUP SUMMIT FOR NIGERIA @65 WITH THE TOPIC:Rule of Law: Systemic Problem. The Way Forward

Protocols

Distinguished ladies and gentlemen, esteemed members of the Media Transformative Group, colleagues from the media, public service, and civil society — good morning.

I thank the organizers for this timely conversation. At sixty-five, Nigeria has matured in many ways — politically, economically, socially. Yet, we still stand at the same moral crossroad that has haunted every generation since independence: the struggle to make law supreme over men, and not men supreme over law.

Our theme today — Rule of Law: Systemic Problem. The Way Forward — could not be more urgent.

1. Understanding the Rule of Law

The rule of law is not merely a legal doctrine; it is the foundation of state legitimacy. It is what transforms power into governance, and governance into justice. But when laws are selectively applied, weakly enforced, or willfully ignored, the very fabric of nationhood begins to unravel.

In Nigeria, the problem is not the absence of laws — it is the failure of laws to deter wrongdoing, to punish fairly, and to inspire trust.

2. The Systemic Nature of the Problem

Our challenge with the rule of law is systemic — rooted in the interlocking weaknesses of our legal framework, justice administration, law enforcement, and public morality.

Let’s look at these in turn.

First, our legal codes are outdated.

The Penal Code, still in force across much of Northern Nigeria, and the Criminal Code, applied in the South, both date back to colonial-era formulations from the early 20th century. These codes were designed for a society that no longer exists — a pre-digital, pre-industrial Nigeria — yet they remain the basis for prosecuting crimes in a modern republic of over 200 million people.

Consequently, many offences carry laughably low penalties that have lost all deterrent power. A fine of ₦500 for public mischief or ₦2,000 for environmental offences means nothing in today’s economy. Our legal system cannot deter crime when the law itself is obsolete.

Second, our court system remains slow, analog, and overburdened. Despite the enactment of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) 2015, which sought to modernize and harmonize criminal procedure, implementation remains uneven across states.

Many states have not domesticated the Act; where they have, the spirit of reform is undermined by weak enforcement, adjournment abuse, and outdated judicial processes. Justice delayed remains justice denied — and millions of Nigerians continue to wait years for verdicts that never come.

Third, our police system is overstretched, undertrained, and ill-equipped. The average Nigerian police officer faces an impossible task — to enforce 21st-century law with 20th-century tools, and 19th-century conditions. Low morale, poor welfare, and lack of forensic or digital capacity mean that investigations are often flawed from the start.

Without credible evidence-gathering, prosecution collapses — and justice, once again, eludes both victim and society. When the enforcers of law feel abandoned, the enforcement of law becomes optional.

3. The Consequence — A Weak Deterrence Culture

The combined effect of these structural weaknesses is the collapse of deterrence. In our society today, the fear of law has been replaced by the confidence of impunity. Citizens no longer believe that wrongdoing has consequences — and, in too many cases, they are right. Political actors disobey court orders. Powerful individuals manipulate due process. And at the lower levels, petty corruption and non-compliance have become normalized.

Because deterrence is low, compliance is low too — and when compliance is low, the cost of enforcement becomes unsustainably high. We are spending more energy chasing offenders than preventing offences. More resources are devoted to reaction than to regulation.

It should not be so. When crime no longer carries consequence, law ceases to command respect — and without respect, even the best laws are just paper..

4. The Role of the Media — Guardian of Accountability

At this point, we must recognize the strategic role of the media. The media remains the oxygen of democracy and the conscience of accountability. Its investigative power, its reach, and its credibility can amplify justice or suffocate it.

The media must do more than merely report infractions; it must educate, interrogate, and illuminate the systemic weaknesses that enable injustice. In an age of disinformation, ethical journalism is not just a professional duty — it is a patriotic act.

5. The Way Forward — From Systemic Problem to Structural Solution

If Nigeria is to entrench the rule of law, reform must move beyond speeches and workshops. We must fix the architecture of justice — not just its furniture.

Let me outline five urgent priorities.

1. Legal Modernization

We must overhaul the Penal Code and Criminal Code to reflect modern realities — including cybercrime, environmental offences, gender-based violence, financial crimes, and digital fraud. Penalties must be realistic and proportionate to current economic and moral standards.

To achieve this, we must strengthen the Nigeria Law Reform Commission (NLRC) — empowering it with the funding, expertise, and political independence needed to continuously review, update, and harmonize Nigeria’s body of laws.

A dynamic society cannot operate under static laws. The NLRC should be repositioned as the central engine of legislative modernization — ensuring that our legal framework evolves in step with social and technological change.

2. Deepen Implementation of the ACJA 2015

Every state must domesticate the ACJA and build capacity for its practical enforcement. Procedural reform must be backed by funding, training, and technology. A digital justice system — e-filing, virtual hearings, case tracking — is no longer optional. It is essential.

3. Professionalize and Modernize Policing

The Nigerian Police Force must transition from a force of reaction to a service of prevention. That means better recruitment, proper training, forensic capacity, welfare reform, and the deployment of technology — from body cameras to criminal databases.

A demoralized police cannot defend a moral society.

4. Strengthen Judicial Independence and Accountability

Judicial appointments, promotions, and discipline must be insulated from political control. At the same time, the judiciary must embrace transparency, performance audits, and digitalization. Independence must not become isolation; accountability must not become interference.

5. Civic and Institutional Reorientation

Finally, we must rebuild the moral contract between citizen and state. Civic education — in schools, in the media, in faith institutions — must teach that the law is not an enemy to evade, but the shield that protects all.

6. What the Tinubu Government is Doing

It is important to acknowledge that the present administration under President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has not ignored these long-standing structural issues.

Indeed, several reform efforts are already underway to strengthen the rule of law, modernize the justice sector, and rebuild institutional trust.

First, the government has demonstrated a clear commitment to fiscal and governance reforms that restore discipline, transparency, and accountability — the foundation of any lawful society. The ongoing public finance reforms, civil service digitization, and retooling of the anti-corruption architecture all contribute indirectly to the culture of compliance that sustains the rule of law.

Second, the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) implementation has received renewed federal support, particularly through collaboration with state governments and development partners to standardize procedures, build capacity, and deploy digital tools that speed up the justice process.

Third, there is a new national drive toward police modernization and professionalization. The Police Reform Roadmap and the Police Trust Fund are being recalibrated to improve welfare, training, and logistics.

Body cameras, digital crime databases, and improved investigative tools are gradually being introduced — small steps, but essential ones.

Fourth, the government, through the Federal Ministry of Justice and the Nigeria Law Reform Commission, has initiated a comprehensive process to review obsolete laws, many of which date back to the colonial era. The aim is to align Nigeria’s laws with modern social, economic, and technological realities.

Finally, the Tinubu administration has reaffirmed its commitment to judicial independence and access to justice. The ongoing dialogue with the judiciary over improved remuneration and working conditions for judges reflects the government’s recognition that justice cannot be strong if its guardians are weak.

Taken together, these measures represent a gradual but deliberate shift — from a culture of impunity to a culture of consequence; from procedural stagnation to systemic renewal.

The task before all of us — policymakers, media, civil society, and citizens — is to sustain these reforms, monitor them, and insist that they deliver not just activity, but impact.

7. Closing Reflections — Building a Culture of Consequence

As we mark Nigeria at 65, our true national project is not simply to grow GDP or build roads. It is to build a culture of consequence — where the law means what it says, and says what it means. Because without consequence, there can be no justice.

Without justice, there can be no peace. And without peace, there can be no progress. The rule of law is not the responsibility of judges alone — it is the collective conscience of all who believe that no nation can be greater than its respect for justice.

Let us, therefore, resolve that the next 65 years of Nigeria’s story will not be written by the rule of men, but by the rule of law.

Thank you, and God bless the Federal Republic of Nigeria.