From Fame to Frustration: Why So Many Nigerian Ex-Internationals End Up Broke

From Fame to Frustration: Why So Many Nigerian Ex-Internationals End Up Broke

For decades, Nigerian footballers have been celebrated as national treasures. They rose from dusty pitches to global stadiums, pulling on the green-and-white jersey to the cheers of millions. Some earned millions of dollars in salaries and endorsements, their names sung across Europe and Africa.

Yet, behind the glory lies a disturbing reality: once the cheers fade and the boots are hung, many of these same heroes find themselves struggling to pay bills, abandoned by a system they once lifted to global heights.

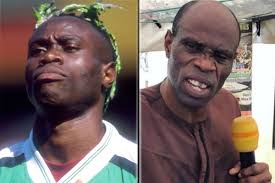

The recent grief-laden words of Taribo West at the burial of legendary goalkeeper Peter Rufai echo a painful truth. Rufai, one of Nigeria’s greatest shot-stoppers in the 1990s, died largely unsupported, left to fend for himself despite his service to the nation. His fate mirrors that of many others—champions on the pitch, forgotten men off it.

So, what happens between the heights of fame and the depths of financial ruin? And who bears responsibility: the state, or the players themselves?

Millions Earned, Millions Lost

The numbers tell a stark story. In 1999, PM Sports reported that Taribo West, then at AC Milan, and Austin “Jay-Jay” Okocha, dazzling at PSG, each earned more than $1.2 million a year—a fortune by Nigerian standards at the time. Okocha turned that fortune into an empire: today his net worth is estimated at up to ₦23 billion, thanks to savvy investments across sectors.

But for every Okocha, there are countless others like Wilson Oruma, who was duped of ₦2 billion in a fraudulent oil deal, or Femi Opabunmi, once Nigeria’s youngest World Cup player, whose career was cut short by glaucoma, leaving him nearly destitute. Even Kingsley Obiekwu, part of Nigeria’s gold-winning Atlanta ’96 squad, admitted he had to drive his car as a commercial taxi to survive.

What explains such brutal financial swings? Analysts point to poor financial advice, lack of investment knowledge, peer pressure to maintain lavish lifestyles, and the psychological shock of moving from dizzying weekly wages to zero income almost overnight.

“Government Owes Them Nothing”

Not everyone agrees that retired footballers deserve state intervention. Emmanuel Zira, former chairman of Adamawa United, is blunt:

“They were paid handsomely. Instead of investing wisely, many bought bulletproof cars, private jets, and lived in expensive hotels. Why should Nigeria take care of them now? Their earnings didn’t even pass through our banking system to boost the economy—they cashed it abroad and changed it on the black market.”

For Zira, the comparison with other professions is telling. A Nigerian lecturer may work 35 years to earn about ₦105 million total—less than what many footballers pocketed from just a few tournaments. “Football is like every other career. You don’t keep paying a bricklayer forever just because he built a good house for you,” he says.

Former Golden Eaglets coach Fanny Amun agrees:

“When we were active, the federation took care of us. It was a trade-off. Retirement struggles come from poor planning, not neglect.”

A Call for Shared Responsibility

But others, like Prince Harrison Jalla, chairman of the Professional Footballers Association of Nigeria (PFAN) task force, argue differently. He insists that welfare for footballers is not charity—it is a right. FIFA disburses funds annually to member federations, and in his view, a percentage should be earmarked for players’ welfare through collective bargaining.

“Given the short career span and precarious nature of sports, safety nets must exist. Around the world, unions negotiate pensions and support structures. Why not in Nigeria?” Jalla asks.

Without such structures, many ex-players end up at the mercy of chance.

The Teachers’ Comparison

To grasp the scale of imbalance, compare footballers to teachers. A lecturer’s ₦250,000 monthly salary barely sustains a modest life, and after decades of service, retirement benefits are meagre. Yet, a footballer could earn $10,000 per match in bonuses alone, plus allowances, sponsorships, and prize money.

The problem, critics say, is that too many Nigerian stars lived as though the good times would never end. When retirement came—often at 30 or 35—they were unprepared.

Former Eagles striker Brown Ideye goes as far as saying broke ex-footballers should be jailed:

“Footballers, start saving from day one. No excuses. Your wages are your lifetime salary crammed into a few years. If you blow it and can’t feed yourself after retirement, that’s on you.”

The Other Side: Success Stories

Thankfully, not all stories are bleak. Nwankwo Kanu established the Kanu Heart Foundation, saving lives while building businesses. Yakubu Aiyegbeni reinvented himself as a football agent and businessman. Obafemi Martins owns real estate, nightclubs, and a clothing brand. Vincent Enyeama runs a thriving hotel in Uyo. John Mikel Obi has diversified into transport, media, and endorsements.

Their examples underline a critical truth: with the right planning and networks, footballers can thrive long after retirement.

Lessons from Painful Mistakes

The cautionary tales are equally instructive. Daniel Amokachi once owned a private jet, but quickly returned it when the maintenance costs nearly ruined him. “If I had kept the plane, it would have been seized eventually,” he admitted. That decision may have saved his financial future.

The message is clear: wealth is fleeting without wisdom.

The Way Forward

The plight of ex-internationals is a complex puzzle. The government, federations, and unions do owe some structural duty of care, especially given the billions football generates globally. But players also carry heavy responsibility: to plan wisely, seek financial education, and resist the temptations of excess.

Football, after all, is a short career with a long afterlife. The glory may fade, but smart choices can ensure the wealth endures.

As Nigeria continues to celebrate new stars, the haunting stories of yesterday’s heroes should serve as a warning: the roar of the crowd eventually fades, but the bills never do.

By Haruna Yakubu Haruna